| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 16th Vice President of the United States 17th President of the United States Vice presidential and Presidential campaigns Post-presidency Family  |

||

Andrew Johnson, who became the 17th U.S. president following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was one of the last U.S. Presidents to personally own slaves.[a] Johnson also oversaw the first years of the Reconstruction era as the head of the executive branch of the U.S. government. This professional obligation clashed with Johnson's long-held personal resentments: "Johnson's attitudes showed much consistency. All of his life he held deep-seated Jacksonian convictions along with prejudices against blacks, sectionalists, and the wealthy."[2] Johnson's engagement with Southern Unionism and Abraham Lincoln is summarized by his statement, "Damn the negroes; I am fighting these traitorous aristocrats, their masters!"[2]

According to Reconstruction historian Manisha Sinha, Johnson is remembered today for making white supremacy the overriding principle of his presidency through "his obdurate opposition to Reconstruction, the project to establish an interracial democracy in the United States after the destruction of slavery. He wanted to prevent, as he put it, the 'Africanization' of the country. Under the guise of strict constructionism, states' rights and opposition to big government, previously deployed by Southern slaveholders to defend slavery, Johnson vetoed all federal laws intended to protect former slaves from racial terror and from the Black Codes passed in the old Confederate states. This reduced African-Americans to a state of semi-servitude. Johnson peddled the racist myth that Southern whites were victimized by black emancipation and citizenship, which became an article of faith among Lost Cause proponents in the postwar South."[3]

In 1935, W. E. B. DuBois included an essay called "Transubstantiation of a Poor White" in his book Black Reconstruction in America. The topic was Johnson's Presidential Reconstruction, about which DuBois wrote: "Andrew Johnson could not include Negroes in any conceivable democracy. He tried to, but as a poor white, steeped in the limitations, prejudices, and ambitions of his social class, he could not; and this is the key to his career...For [the future of the] Negroes...he had nothing...except the bare possibility that, if given freedom, they might continue to exist and not die out."[4]

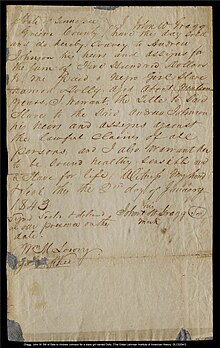

- ^ "Bill of sale to Andrew Johnson for a slave girl named Dolly". Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Greene County, Tenn. 1843. GLC02041. Retrieved 2023-05-03.

- ^ a b Cimprich, John (1980). "Military Governor Johnson and Tennessee Blacks, 1862-65". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 39 (4): 459–470. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42626128.

- ^ Sinha, Manisha (November 29, 2019). "Donald Trump, Meet Your Precursor". Opinion. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ DuBois, W.E.B. (1935). "Transubstantiation of a Poor White". Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1888. New York: Russell. pp. 242–244 – via Internet Archive.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).