The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons.

The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the ninth century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great (r. 871–899). Its content, which incorporated sources now otherwise lost dating from as early as the seventh century, is known as the "Common Stock" of the Chronicle.[2] Multiple copies were made of that one original and then distributed to monasteries across England, where they were updated, partly independently. These manuscripts collectively are known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Almost all of the material in the Chronicle is in the form of annals, by year; the earliest is dated at 60 BC (the annals' date for Caesar's invasions of Britain). In one case, the Chronicle was still being actively updated in 1154.

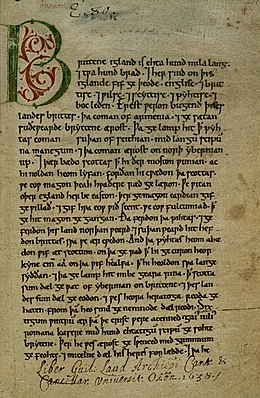

Nine manuscripts of the Chronicle, none of which is the original, survive in whole or in part. Seven are held in the British Library, one in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, and the oldest in the Parker Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. The oldest seems to have been started towards the end of Alfred's reign, while the most recent was copied at Peterborough Abbey after a fire at that monastery in 1116. Some later medieval chronicles deriving from lost manuscripts contribute occasional further hints concerning Chronicle material.

Both because much of the information given in the Chronicle is not recorded elsewhere and because of the relatively clear chronological framework it provides for understanding events, the Chronicle is among the most influential historical sources for England between the collapse of Roman authority and the decades following the Norman Conquest;[3] Nicholas Howe called it and Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People "the two great Anglo-Saxon works of history".[4] The Chronicle's accounts tend to be highly politicised, with the Common Stock intended primarily to legitimise the dynasty and reign of Alfred the Great. Comparison between Chronicle manuscripts and with other medieval sources demonstrates that the scribes who copied or added to them omitted events or told one-sided versions of them, often providing useful insights into early medieval English politics.

The Chronicle manuscripts are also important sources for the history of the English language;[3] in particular, in annals from 1131 onwards, the later Peterborough text provides key evidence for the transition from the standard Old English literary language to early Middle English, containing some of the earliest known Middle English text.[5]