| Antihistamine | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

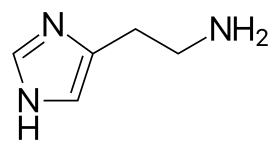

Histamine structure | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Pronunciation | /ˌæntiˈhɪstəmiːn/ |

| ATC code | R06 |

| Mechanism of action | • Receptor antagonist • Inverse agonist |

| Biological target | Histamine receptors • HRH1 • HRH2 • HRH3 • HRH4 |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D006633 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Antihistamines are drugs which treat allergic rhinitis, common cold, influenza, and other allergies.[1] Typically, people take antihistamines as an inexpensive, generic (not patented) drug that can be bought without a prescription and provides relief from nasal congestion, sneezing, or hives caused by pollen, dust mites, or animal allergy with few side effects.[1] Antihistamines are usually for short-term treatment.[1] Chronic allergies increase the risk of health problems which antihistamines might not treat, including asthma, sinusitis, and lower respiratory tract infection.[1] Consultation of a medical professional is recommended for those who intend to take antihistamines for longer-term use.[1]

Although the general public typically uses the word "antihistamine" to describe drugs for treating allergies, physicians and scientists use the term to describe a class of drug that opposes the activity of histamine receptors in the body.[2] In this sense of the word, antihistamines are subclassified according to the histamine receptor that they act upon. The two largest classes of antihistamines are H1-antihistamines and H2-antihistamines.

H1-antihistamines work by binding to histamine H1 receptors in mast cells, smooth muscle, and endothelium in the body as well as in the tuberomammillary nucleus in the brain. Antihistamines that target the histamine H1-receptor are used to treat allergic reactions in the nose (e.g., itching, runny nose, and sneezing). In addition, they may be used to treat insomnia, motion sickness, or vertigo caused by problems with the inner ear. H2-antihistamines bind to histamine H2 receptors in the upper gastrointestinal tract, primarily in the stomach. Antihistamines that target the histamine H2-receptor are used to treat gastric acid conditions (e.g., peptic ulcers and acid reflux). Other antihistamines also target H3 receptors and H4 receptors.

Histamine receptors exhibit constitutive activity, so antihistamines can function as either a neutral receptor antagonist or an inverse agonist at histamine receptors.[2][3][4][5] Only a few currently marketed H1-antihistamines are known to function as antagonists.[2][5]

- ^ a b c d e Consumer Reports (2013), Using Antihistamines to Treat Allergies, Hay Fever, & Hives - Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price (PDF), Yonkers, New York: Consumer Reports, archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017, retrieved 29 June 2017

- ^ a b c Canonica GW, Blaiss M (2011). "Antihistaminic, anti-inflammatory, and antiallergic properties of the nonsedating second-generation antihistamine desloratadine: a review of the evidence". World Allergy Organ J. 4 (2): 47–53. doi:10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182093e19. PMC 3500039. PMID 23268457.

The H1-receptor is a transmembrane protein belonging to the G-protein coupled receptor family. Signal transduction from the extracellular to the intracellular environment occurs as the GCPR becomes activated after binding of a specific ligand or agonist. A subunit of the G-protein subsequently dissociates and affects intracellular messaging including downstream signaling accomplished through various intermediaries such as cyclic AMP, cyclic GMP, calcium, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), a ubiquitous transcription factor thought to play an important role in immune-cell chemotaxis, proinflammatory cytokine production, expression of cell adhesion molecules, and other allergic and inflammatory conditions.1,8,12,30–32 ... For example, the H1-receptor promotes NF-κB in both a constitutive and agonist-dependent manner and all clinically available H1-antihistamines inhibit constitutive H1-receptor-mediated NF-κB production ...

Importantly, because antihistamines can theoretically behave as inverse agonists or neutral antagonists, they are more properly described as H1-antihistamines rather than H1-receptor antagonists.15 - ^ Panula P, Chazot PL, Cowart M, et al. (2015). "International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCVIII. Histamine Receptors". Pharmacol. Rev. 67 (3): 601–55. doi:10.1124/pr.114.010249. PMC 4485016. PMID 26084539.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Inverse agonists vs antagonistswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "H1 receptor". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. Retrieved 8 October 2015.