Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs, also known as antinuclear factor or ANF)[2] are autoantibodies that bind to contents of the cell nucleus. In normal individuals, the immune system produces antibodies to foreign proteins (antigens) but not to human proteins (autoantigens). In some cases, antibodies to human antigens are produced; these are known as autoantibodies.[3]

There are many subtypes of ANAs such as anti-Ro antibodies, anti-La antibodies, anti-Sm antibodies, anti-nRNP antibodies, anti-Scl-70 antibodies, anti-dsDNA antibodies, anti-histone antibodies, antibodies to nuclear pore complexes, anti-centromere antibodies and anti-sp100 antibodies. Each of these antibody subtypes binds to different proteins or protein complexes within the nucleus. They are found in many disorders including autoimmunity, cancer and infection, with different prevalences of antibodies depending on the condition. This allows the use of ANAs in the diagnosis of some autoimmune disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome,[4] scleroderma,[5] mixed connective tissue disease,[6] polymyositis, dermatomyositis, autoimmune hepatitis[7] and drug-induced lupus.[8]

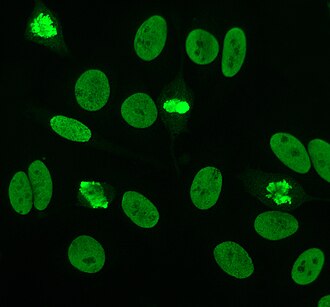

The ANA test detects the autoantibodies present in an individual's blood serum. The common tests used for detecting and quantifying ANAs are indirect immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). In immunofluorescence, the level of autoantibodies is reported as a titre. This is the highest dilution of the serum at which autoantibodies are still detectable. Positive autoantibody titres at a dilution equal to or greater than 1:160 are usually considered as clinically significant. Positive titres of less than 1:160 are present in up to 20% of the healthy population, especially the elderly. Although positive titres of 1:160 or higher are strongly associated with autoimmune disorders, they are also found in 5% of healthy individuals.[9][10] Autoantibody screening is useful in the diagnosis of autoimmune disorders and monitoring levels helps to predict the progression of disease.[8][11][12] A positive ANA test is seldom useful if other clinical or laboratory data supporting a diagnosis are not present.[13]

- ^ Al-Mughales JA (2022). "Anti-Nuclear Antibodies Patterns in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Their Correlation With Other Diagnostic Immunological Parameters". Front Immunol. 13: 850759. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.850759. PMC 8964090. PMID 35359932.

Minor edits by Mikael Häggström, MD

- Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license - ^ "Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Reece, Jane, Campbell, Neil (2005). Biology (7th ed.). San Francisco: Pearson/Benjamin-Cummings. ISBN 978-0805371468.[page needed]

- ^ Cervera R, Font, J, Ramos-Casals, M, García-Carrasco, M, Rosas, J, Morlà, RM, Muñoz, FJ, Artigues, A, Pallarés, L, Ingelmo, M (2000). "Primary Sjögren's syndrome in men: clinical and immunological characteristics". Lupus. 9 (1): 61–4. doi:10.1177/096120330000900111. PMID 10713648. S2CID 39696993.

- ^ Barnett AJ, McNeilage, LJ (May 1993). "Antinuclear antibodies in patients with scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) and in their blood relatives and spouses". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 52 (5): 365–8. doi:10.1136/ard.52.5.365. PMC 1005051. PMID 8323384.

- ^ Burdt MA, Hoffman, Robert W., Deutscher, Susan L., Wang, Grace S., Johnson, Jane C., Sharp, Gordon C. (1 May 1999). "Long-term outcome in mixed connective tissue disease: Longitudinal clinical and serologic findings". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 42 (5): 899–909. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<899::AID-ANR8>3.0.CO;2-L. PMID 10323445.

- ^ Obermayer-Straub P, Strassburg, CP, Manns, MP (2000). "Autoimmune hepatitis". Journal of Hepatology. 32 (1 Suppl): 181–97. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80425-0. PMID 10728804.

- ^ a b Kavanaugh A, Tomar R, Reveille J, Solomon DH, Homburger HA (January 2000). "Guidelines for clinical use of the antinuclear antibody test and tests for specific autoantibodies to nuclear antigens. American College of Pathologists". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 124 (1): 71–81. doi:10.5858/2000-124-0071-GFCUOT. PMID 10629135.

- ^ Tan EM, Feltkamp, TE, Smolen, JS, Butcher, B, Dawkins, R, Fritzler, MJ, Gordon, T, Hardin, JA, Kalden, JR, Lahita, RG, Maini, RN, McDougal, JS, Rothfield, NF, Smeenk, RJ, Takasaki, Y, Wiik, A, Wilson, MR, Koziol, JA (September 1997). "Range of antinuclear antibodies in "healthy" individuals". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 40 (9): 1601–11. doi:10.1002/art.1780400909. PMID 9324014.

- ^ "The Antinuclear Antibody Test: What It Means". Lupus Foundation of America. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ Kumar Y, Bhatia, A, Minz, RW (Jan 2, 2009). "Antinuclear antibodies and their detection methods in diagnosis of connective tissue diseases: a journey revisited". Diagnostic Pathology. 4: 1. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-4-1. PMC 2628865. PMID 19121207.

- ^ Yamamoto K (January 2003). "Pathogenesis of Sjögren's syndrome". Autoimmun Rev. 2 (1): 13–8. doi:10.1016/S1568-9972(02)00121-0. PMID 12848970.

- ^ Richardson B, Epstein, WV (September 1981). "Utility of the fluorescent antinuclear antibody test in a single patient". Annals of Internal Medicine. 95 (3): 333–8. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-95-3-333. PMID 7023311.