The art of the Crusades, produced in the Levant under Latin rulership, spanned two artistic periods in Europe, the Romanesque and the Gothic, but in the Crusader states the Gothic style barely appeared. The military crusaders themselves were mostly interested in artistic and development matters, or sophisticated in their taste, and much of their art was destroyed in the loss of their kingdoms so that only a few pieces survive today. Probably their most notable and influential artistic achievement was the Crusader castles, many of which achieve a stark, massive beauty. They developed the Byzantine methods of city-fortification for stand-alone castles far larger than any constructed before, either locally or in Europe.

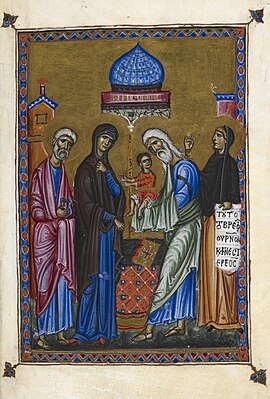

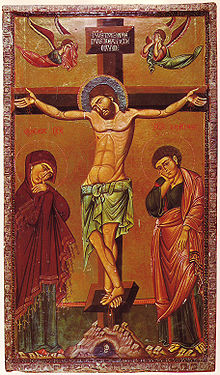

The crusaders encountered a long and rich artistic tradition in the lands they conquered at the end of the 11th century and the beginning of the 12th. Byzantine and Islamic art (that of both the Arabs and the Turks) were the dominant styles in the Crusader states, although there were also the styles of the indigenous Syrians and Armenians. These indigenous styles were incorporated into styles brought by the crusaders from Europe, which were themselves highly varied, stemming from France, Italy, Germany, England, and elsewhere. On the whole the Eastern Christian styles were more significant influences than Islamic art; the artists working in the Crusader lands are assumed to have had the same variety of backgrounds. Many art historians attempt to guess the backgrounds, in terms of ethnicity, place of birth and training, of the artists involved with particular works, an effort treated with caution by Kurt Weitzmann, Doula Mouriki, and Jaroslav Folda, author of the most recent detailed survey.[1]

Crusader art in the Levant, like the history of the Crusader kingdoms in general, falls clearly into two, or three, periods. The first begins with the First Crusade which culminated in 1099 with the bloody taking of Jerusalem and the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other states to the north. The following decades were turbulent but artistically productive, until the catastrophe of 1187 saw the Crusader defeat at the Battle of Hattin and the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin. In the second period the Kingdom of Jerusalem was now hugely reduced in size to control only a few coastal towns and the areas around them, which were gradually whittled away by the Muslims until the final Siege of Acre (1291) ended Crusader presence in the Levant. However the kingdom still controlled Cyprus, taken from the Byzantine Empire, and the House of Lusignan continued to rule there, and later the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, until respectively 1489 and the late 14th century, representing the third period of Crusader art, not counted as such by all sources; in Cyprus the Gothic style is often found.[2]

There is a further sense of "Crusader art" to cover the art produced in the Latin Empire that usurped much of the Byzantine Empire, ruled by the Crusaders between the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade and 1261. Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai was also a centre during this time, and perhaps later. This art had a larger impact in Europe, to which many artists probably returned after the collapse of the regime, influencing Italo-Byzantine painting there. The crusades were also important as a subject in Western art, mainly in illuminated luxury versions of the many histories that were popular reading with Western elites.

- ^ Folda, I, 13, quoting Weitzmann; I, 17–18, quoting Mouriki; Hunt, Lucy-Anne (1991). "Art and Colonialism: The Mosaics of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (1169) and the Problem of "Crusader" Art". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 45: 69–85. doi:10.2307/1291693. JSTOR 1291693.

- ^ Folda restricts himself to the art of the "Holy Land" or "Syria-Palestine", Folda, I, 19-20