| Assassination of Queen Min | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the prelude to the Japanese annexation of Korea | |||||||

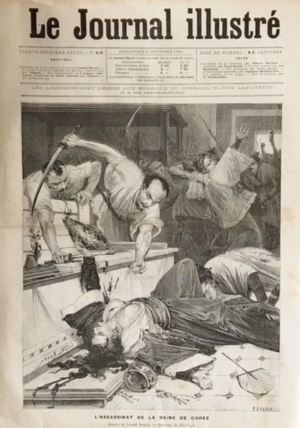

Le Journal illustré cover depicting the assassination (1895) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Japanese Legation Security Group Hullyeondae: 1,000 48 ronin | Capital Guards (Siwidae): 300–400 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown military casualties but many court ladies, eunuchs, and officials killed or wounded. | |||||||

Around 6 a.m. on 8 October 1895, Queen Min, the consort of the Korean monarch Gojong, was assassinated by a group of Japanese agents under Miura Gorō. After her death, she was posthumously given the title of "Empress Myeongseong". The attack happened at the royal palace Gyeongbokgung in Seoul, Joseon. This incident is known in Korea as the Eulmi Incident.[a]

By the time of her death, the queen had acquired arguably more political power than even her husband.[2] Through this process, she made many enemies and escaped a number of assassination attempts. Among her opponents were the king's father the Heungseon Daewongun, the pro-Japanese ministers of the court, and the Korean army regiment that had been trained by Japan: the Hullyeondae. Weeks before her death, Japan replaced their emissary to Korea with a new one: Miura Gorō. Miura was a former military man who professed to being inexperienced in diplomacy, and reportedly found dealing with the powerful queen frustrating.[3] After the queen began to align Korea with the Russian Empire to offset Japanese influence, Miura struck a deal with Adachi Kenzō of the newspaper Kanjō shinpō and the Daewongun to carry out her killing.[4][5]

The agents were let into the palace by pro-Japanese Korean guards. Once inside, they beat and threatened the royal family and the occupants of the palace during their search for the queen. Women were dragged by the hair and thrown down stairs, off verandas, and out of windows. Two women suspected of being the queen were killed. When the queen was eventually located, her killer jumped on her chest three times, then cleaved her head with a sword.[6][7] Some assassins looted the palace, while others covered her corpse in oil and burned it.[6]

The Japanese government arrested the assassins on charges of murder and conspiracy to commit murder. Non-Japanese witnesses were not called,[8] and the court disregarded evidence from Japanese investigators, who had recommended that the assassins be found guilty.[9] The defendants were acquitted of all charges, despite the court acknowledging that the defendants had conspired to commit murder.[10] Miura went on to have a career in the Japanese government, where he eventually became Minister of Communications.

The killing and trial sparked domestic and international shock and outrage.[8][11][12] Sentiment shifted against Japan in Korea; the king fled for protection in the Russian legation and anti-Japanese militias rose throughout the peninsula. While the attack harmed Japan's position in Korea in the short run, it did not prevent Korea's eventual colonization in 1910.

- ^ "다시 을미년(乙未年)이다" [It's the Eulmi Year Again]. JoongAng Ilbo (in Korean). 29 December 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ Orbach 2016, p. 103.

- ^ Orbach 2016, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Keene 2002, p. 515.

- ^ Keene 2002, pp. 514–515.

- ^ a b Keene 2002, p. 517.

- ^ Jager 2023, p. 209.

- ^ a b Orbach 2016, p. 123.

- ^ Orbach 2016, p. 121.

- ^ Orbach 2016, p. 122.

- ^ Jager 2023, p. 210.

- ^ Underwood 1904, pp. 150–152.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).