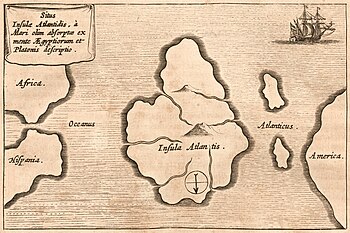

Atlantis (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, romanized: Atlantìs nêsos, lit. 'island of Atlas') is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works Timaeus and Critias as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world,[1][2] making it the literary counter-image of the Achaemenid Empire.[3] After an ill-fated attempt to conquer "Ancient Athens," Atlantis falls out of favor with the deities and submerges into the Atlantic Ocean. Since Plato describes Athens as resembling his ideal state in the Republic, the Atlantis story is meant to bear witness to the superiority of his concept of a state.[4][5]

Despite its minor importance in Plato's work, the Atlantis story has had a considerable impact on literature. The allegorical aspect of Atlantis was taken up in utopian works of several Renaissance writers, such as Francis Bacon's New Atlantis and Thomas More's Utopia.[6][7] On the other hand, nineteenth-century amateur scholars misinterpreted Plato's narrative as historical tradition, most famously Ignatius L. Donnelly in his Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. Plato's vague indications of the time of the events (more than 9,000 years before his time[8]) and the alleged location of Atlantis ("beyond the Pillars of Hercules") gave rise to much pseudoscientific speculation.[9] As a consequence, Atlantis has become a byword for any and all supposed advanced prehistoric lost civilizations and continues to inspire contemporary fiction, from comic books to films.

While present-day philologists and classicists agree on the story's fictional nature,[10][11] there is still debate on what served as its inspiration. Plato is known to have freely borrowed some of his allegories and metaphors from older traditions, as he did with the story of Gyges.[12] This led a number of scholars to suggest possible inspiration of Atlantis from Egyptian records of the Thera eruption,[13][14] the Sea Peoples invasion,[15] or the Trojan War.[16] Others have rejected this chain of tradition as implausible and insist that Plato created an entirely fictional account,[17][18][19] drawing loose inspiration from contemporary events such as the failed Athenian invasion of Sicily in 415–413 BC or the destruction of Helike in 373 BC.[20]

- ^ Plato's contemporaries pictured the world as consisting of only Europe, Northern Africa, and Western Asia (see the map of Hecataeus of Miletus).

- ^ Hale, John R. (2009). Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy. New York: Penguin. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-670-02080-5.

Plato also wrote the myth of Atlantis as an allegory of the archetypal thalassocracy or naval power.

- ^ Welliver, Warman (1977). Character, Plot and Thought in Plato's Timaeus-Critias. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 42. ISBN 978-90-04-04870-6.

- ^ Hackforth, R. (1944). "The Story of Atlantis: Its Purpose and Its Moral". Classical Review. 58 (1): 7–9. doi:10.1017/s0009840x00089356. ISSN 0009-840X. JSTOR 701961. S2CID 162292186.

- ^ David, Ephraim (1984). "The Problem of Representing Plato's Ideal State in Action". Riv. Fil. 112: 33–53.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis (1965). "Utopia, the City and the Machine". Daedalus. 94 (2): 271–292. JSTOR 20026910.

- ^ Hartmann, Anna-Maria (2015). "The Strange Antiquity of Francis Bacon's New Atlantis". Renaissance Studies. 29 (3): 375–393. doi:10.1111/rest.12084. S2CID 161272260.

- ^ The frame story in Critias tells about an alleged visit of the Athenian lawmaker Solon (c. 638 BC – 558 BC) to Egypt, where he was told the Atlantis story that supposedly occurred 9,000 years before his time.

- ^ Feder, Kenneth (2011). "Lost: One Continent - Reward". Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology (Seventh ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 141–164. ISBN 978-0-07-811697-1.

- ^ Clay, Diskin (2000). "The Invention of Atlantis: The Anatomy of a Fiction". In Cleary, John J.; Gurtler, Gary M. (eds.). Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy. Vol. 15. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-90-04-11704-4.

- ^ "As Smith discusses in the opening article in this theme issue, the lost island-continent was – in all likelihood – entirely Plato's invention for the purposes of illustrating arguments around Grecian polity. Archaeologists broadly agree with the view that Atlantis is quite simply 'utopia' (Doumas, 2007), a stance also taken by classical philologists, who interpret Atlantis as a metaphorical rather than an actual place (Broadie, 2013; Gill, 1979; Nesselrath, 2002). One might consider the question as being already reasonably solved but despite the general expert consensus on the matter, countless attempts have been made at finding Atlantis." (Dawson & Hayward, 2016)

- ^ Laird, A. (2001). "Ringing the Changes on Gyges: Philosophy and the Formation of Fiction in Plato's Republic". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 121: 12–29. doi:10.2307/631825. JSTOR 631825. S2CID 170951759.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lucewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Griffiths, J. Gwyn (1985). "Atlantis and Egypt". Historia. 34 (1): 3–28. JSTOR 4435908.

- ^ Görgemanns, Herwig (2000). "Wahrheit und Fiktion in Platons Atlantis-Erzählung". Hermes. 128 (4): 405–419. JSTOR 4477385.

- ^ Zangger, Eberhard (1993). "Plato's Atlantis Account – A Distorted Recollection of the Trojan War". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 12 (1): 77–87. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1993.tb00283.x.

- ^ Gill, Christopher (1979). "Plato's Atlantis Story and the Birth of Fiction". Philosophy and Literature. 3 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1353/phl.1979.0005. S2CID 170851163.

- ^ Naddaf, Gerard (1994). "The Atlantis Myth: An Introduction to Plato's Later Philosophy of History". Phoenix. 48 (3): 189–209. doi:10.2307/3693746. JSTOR 3693746.

- ^ Morgan, K. A. (1998). "Designer History: Plato's Atlantis Story and Fourth-Century Ideology". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 118 (1): 101–118. doi:10.2307/632233. JSTOR 632233. S2CID 162318214.

- ^ Plato's Timaeus is usually dated 360 BC; it was followed by his Critias.