| Axon | |

|---|---|

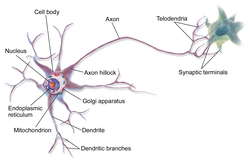

An axon of a multipolar neuron | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D001369 |

| FMA | 67308 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

An axon (from Greek ἄξων áxōn, axis) or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see spelling differences) is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, in vertebrates, that typically conducts electrical impulses known as action potentials away from the nerve cell body. The function of the axon is to transmit information to different neurons, muscles, and glands. In certain sensory neurons (pseudounipolar neurons), such as those for touch and warmth, the axons are called afferent nerve fibers and the electrical impulse travels along these from the periphery to the cell body and from the cell body to the spinal cord along another branch of the same axon. Axon dysfunction can be the cause of many inherited and acquired neurological disorders that affect both the peripheral and central neurons. Nerve fibers are classed into three types – group A nerve fibers, group B nerve fibers, and group C nerve fibers. Groups A and B are myelinated, and group C are unmyelinated. These groups include both sensory fibers and motor fibers. Another classification groups only the sensory fibers as Type I, Type II, Type III, and Type IV.

An axon is one of two types of cytoplasmic protrusions from the cell body of a neuron; the other type is a dendrite. Axons are distinguished from dendrites by several features, including shape (dendrites often taper while axons usually maintain a constant radius), length (dendrites are restricted to a small region around the cell body while axons can be much longer), and function (dendrites receive signals whereas axons transmit them). Some types of neurons have no axon and transmit signals from their dendrites. In some species, axons can emanate from dendrites known as axon-carrying dendrites.[1] No neuron ever has more than one axon; however in invertebrates such as insects or leeches the axon sometimes consists of several regions that function more or less independently of each other.[2]

Axons are covered by a membrane known as an axolemma; the cytoplasm of an axon is called axoplasm. Most axons branch, in some cases very profusely. The end branches of an axon are called telodendria. The swollen end of a telodendron is known as the axon terminal or end-foot which joins the dendrite or cell body of another neuron forming a synaptic connection. Axons usually make contact with other neurons at junctions called synapses but can also make contact with muscle or gland cells. In some circumstances, the axon of one neuron may form a synapse with the dendrites of the same neuron, resulting in an autapse. At a synapse, the membrane of the axon closely adjoins the membrane of the target cell, and special molecular structures serve to transmit electrical or electrochemical signals across the gap. Some synaptic junctions appear along the length of an axon as it extends; these are called en passant boutons ("in passing boutons") and can be in the hundreds or even the thousands along one axon.[3] Other synapses appear as terminals at the ends of axonal branches.

A single axon, with all its branches taken together, can target multiple parts of the brain and generate thousands of synaptic terminals. A bundle of axons make a nerve tract in the central nervous system,[4] and a fascicle in the peripheral nervous system. In placental mammals the largest white matter tract in the brain is the corpus callosum, formed of some 200 million axons in the human brain.[4]

- ^ Triarhou LC (2014). "Axons emanating from dendrites: phylogenetic repercussions with Cajalian hues". Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 8: 133. doi:10.3389/fnana.2014.00133. PMC 4235383. PMID 25477788.

- ^ Yau KW (December 1976). "Receptive fields, geometry and conduction block of sensory neurones in the central nervous system of the leech". The Journal of Physiology. 263 (3): 513–38. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011643. PMC 1307715. PMID 1018277.

- ^ Squire, Larry (2013). Fundamental neuroscience (4th ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-0-12-385-870-2.

- ^ a b Luders E, Thompson PM, Toga AW (August 2010). "The development of the corpus callosum in the healthy human brain". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (33): 10985–90. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5122-09.2010. PMC 3197828. PMID 20720105.