Baldwin's rules in organic chemistry are a series of guidelines outlining the relative favorabilities of ring closure reactions in alicyclic compounds. They were first proposed by Jack Baldwin in 1976.[1][2]

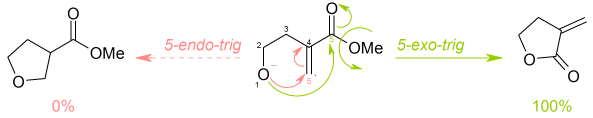

Baldwin's rules discuss the relative rates of ring closures of these various types. These terms are not meant to describe the absolute probability that a reaction will or will not take place, rather they are used in a relative sense. A reaction that is disfavoured (slow) does not have a rate that is able to compete effectively with an alternative reaction that is favoured (fast). However, the disfavoured product may be observed, if no alternate reactions are more favoured.

The rules classify ring closures in three ways:

- the number of atoms in the newly formed ring

- into exo and endo ring closures, depending whether the bond broken during the ring closure is inside (endo) or outside (exo) the ring that is being formed

- into tet, trig and dig geometry of the atom being attacked, depending on whether this electrophilic carbon is tetrahedral (sp3 hybridised), trigonal (sp2 hybridised) or diagonal (sp hybridised).

Thus, a ring closure reaction could be classified as, for example, a 5-exo-trig.

Baldwin discovered that orbital overlap requirements for the formation of bonds favour only certain combinations of ring size and the exo/endo/dig/trig/tet parameters.

There are sometimes exceptions to Baldwin's rules. For example, cations often disobey Baldwin's rules, as do reactions in which a third-row atom is included in the ring. An expanded and revised version of the rules is available:[3]

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||||

| type | exo | endo | exo | endo | exo | endo | exo | endo | exo | endo |

| tet | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ||

| trig | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| dig | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

The rules apply when the nucleophile can attack the bond in question in an ideal angle. These angles are 180° (Walden inversion) for exo-tet reactions, 109° (Bürgi–Dunitz angle) for exo-trig reaction and 120° for endo-dig reactions. Angles for nucleophilic attack on alkynes were reviewed and redefined recently.[4] The "acute angle" of attack postulated by Baldwin was replaced with a trajectory similar to the Bürgi–Dunitz angle.[5]

- ^ Jack E. Baldwin (1976). "Rules for Ring Closure". J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. (18): 734–736. doi:10.1039/C39760000734.(Open access)

- ^ Baldwin, J. E.; et al. (1977). "Rules for Ring Closure: Ring Formation by Conjugate Addition of Oxygen Nucleophiles". J. Org. Chem. 42 (24): 3846. doi:10.1021/jo00444a011.

- ^ The Baldwin Rules: Revised and Extended. Gilmore, K; Mohamed, R. K.; Alabugin, I. V. WIREs: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2016, 6, 487–514. http://wires.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WiresArticle/wisId-WCMS1261.html doi:10.1002/wcms.1261

- ^ Gilmore, K.; Alabugin, I. V. Cyclizations of Alkynes: Revisiting Baldwin's Rules for Ring Closure. Chem. Rev. 2011. 111, 6513–6556. doi:10.1021/cr200164y

- ^ Alabugin, I. Gilmore, K.; Manoharan, M. Rules for Anionic and Radical Ring Closure of Alkynes. J. Am. Chem.Soc. 2011, 133, 12608-12623, doi:10.1021/ja203191f