| Beheadings of Moca | |

|---|---|

| Part of Siege of Santo Domingo (1805) | |

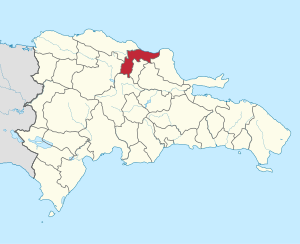

Espaillat in the Dominican Republic | |

| Location | Santo Domingo |

| Date | 3 April 1805 – 28 April 1805 |

| Target | Jean-Louis Ferrand and his troops, Dominicans. |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Weapons | Bayonets, machetes, axes, firearms, swords |

| Deaths | 500 (at Moca),[1] 400 at Santiago[2] |

| Victims | Civilians of Santo Domingo |

| Perpetrators | Army of the First Empire of Haiti |

| Motive | Reprisal[1][2] |

The Beheadings of Moca (Spanish: Degüello de Moca; French: Décapitation de Moca; Haitian Creole: Masak nan Moca)[3] was a massacre that took place in Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) in April 1805 when the invading Haitian army attacked civilians as ordered by Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe, during their retreat to Haiti after the failed attempt to end French rule in Santo Domingo. The event was narrated by survivor Gaspar Arredondo y Pichardo in his book Memoria de mi salida de la isla de Santo Domingo el 28 de abril de 1805 (Memory of my departure from the island of Santo Domingo on April 28, 1805), which was written nearly 40 years after the massacre is said to have taken place.[4][5] The broader invasion was part of a series of Haitian invasions into Santo Domingo, and occurred after the return from the Siege of Santo Domingo (1805).[6] Haitian historian Jean Price-Mars wrote that the troops killed the inhabitants of the targeted settlements irrespective of race.[7]

The raids, carried out by the Haitian invasion force, were headed by Henri Christophe and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who were present during the actions. Municipalities of Santo Domingo (Monte Plata, Cotuí, La Vega, Santiago, Moca, San Jose de las Matas, Monte Cristi, and San Juan de la Maguana) were burned, with reported massacres in Santiago and Moca and the killing of 500 civilians in Moca[1] and another 400 in Santiago[2] after an aborted attempt to expel the French forces led by Jean-Louis Ferrand. Ferrand would later be defeated by Juan Sánchez Ramírez in the Battle of Palo Hincado, after which he committed suicide with his own pistol.[8][2]

- ^ a b c Schoenrich, Otto (2013). Santo Domingo A Country with a Future. ISBN 978-3-8491-9198-6. OCLC 863932373.

- ^ a b c d Pons, Frank Moya (1991). "The Haitian Revolution in Santo Domingo (1789-1809)". Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas. 28 (1). Boehlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H. & Co. KG: 155. doi:10.7767/jbla.1991.28.1.125. ISSN 2194-3680.

- ^ Temboury, Francisco Javier (2016). El habla de Santo Domingo. Punto Rojo Libros S.L. p. 158. ISBN 978-8-416-97902-8.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Marte 2017 p.208was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Arredondo y Pichardo, Gaspar de (2008). Memoria de mi salida de la isla de Santo Domingo el 28 de abril de 1805.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Sagás Inoa 2003 p.was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Price-Mars, Jean (1953). La República de Haití y La República Dominicana (PDF).

- ^ Southley, Captain Thomas (1827). Chronological History of the West Indies. p. 421.