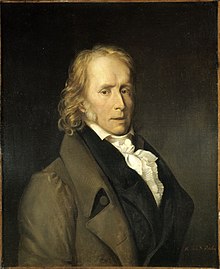

Benjamin Constant | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Hercule de Roche, c. 1820 | |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 14 April 1819 – 8 December 1830 | |

| Constituency | Sarthe (1819–24) Seine 4th (1824–27) Bas-Rhin 1st (1827–30) |

| Member of the Council of State | |

| In office 20 April 1815 – 8 July 1815 | |

| Appointed by | Napoleon I |

| Member of the Tribunat | |

| In office 25 December 1799 – 27 March 1802 | |

| Constituency | Léman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque 25 October 1767 Lausanne, Swiss Confederacy |

| Died | 8 December 1830 (aged 63) Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Nationality | Swiss and French[1] |

| Political party | Republican (1799–1802) Liberals (1819–24) Liberal Party (Bourbon Restoration)#Decline (1824–30) |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh University of Erlangen |

| Profession |

|

| Writing career | |

| Period | 18th and 19th centuries |

| Genre | Prose, essays, pamphlets |

| Subject | Political theory, liberalism, religion, romantic love |

| Literary movement | Romanticism, classical liberalism[2] |

| Years active | 1792–1830 |

| Notable works |

|

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (French: [kɔ̃stɑ̃]; 25 October 1767 – 8 December 1830), or simply Benjamin Constant, was a Swiss political thinker, activist and writer on political theory and religion.

A committed republican from 1795, he backed the coup d'état of 18 Fructidor (4 September 1797) and the following one on 18 Brumaire (9 November 1799). During the Consulat, in 1800 he became the leader of the Liberal Opposition. Having upset Napoleon and left France to go to Switzerland then to the Kingdom of Saxony, Constant nonetheless sided with him during the Hundred Days and became politically active again during the French Restoration. He was elected Député in 1818 and remained in post until his death in 1830. Head of the Liberal opposition, known as Indépendants, he was one of the most notable orators of the Chamber of Deputies of France, as a proponent of the parliamentary system. During the July Revolution, he was a supporter of Louis Philippe I ascending the throne.

Besides his numerous essays on political and religious themes, Constant also wrote on romantic love. His autobiographical Le Cahier rouge (1807) gives an account of his love for Madame de Staël, whose protégé and collaborator he became, especially in the Coppet circle, and a successful novella, Adolphe (1816), are good examples of his work on this topic.[3]

He was a fervent classical liberal of the early 19th century.[4][5] He refined the concept of liberty, defining it as a condition of existence that allowed the individual to turn away interference from the state or society.[6] His ideas influenced the Trienio Liberal movement in Spain, the Liberal Revolution of 1820 in Portugal, the Greek War of Independence, the November uprising in Poland, the Belgian Revolution, and liberalism in Brazil and Mexico.[citation needed]

- ^ Renée Winegarten (2008). Germaine de Staël and Benjamin Constant. Yale University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0300119251. He was granted French nationality in 1797 according to a law passed in 1790 to restore their citizenship to French people exiled on account of their religion.

- ^ Ralph Raico, Classical Liberalism and the Austrian School, Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2012, p. 222.

- ^ Garonna, Paolo (2010). L'Europe de Coppet – Essai sur l'Europe de demain (in French). Le Mont-sur-Lausanne: LEP Éditions Loisirs et Pėdagogie. p. 42. ISBN 978-2606013691.

- ^ Benjamin Constant: French Liberal Extraordinaire, Mises Institute

- ^ Craiutu, A. (2012) A Virtue for Courageous Minds: Moderation in French Political Thought, 1748–1830, pp. 199, 202–203

- ^ Edmund Fawcett, Liberalism: The Life of an Idea (2nd ed. 2018) pp. 33–48