A biological rule or biological law is a generalized law, principle, or rule of thumb formulated to describe patterns observed in living organisms. Biological rules and laws are often developed as succinct, broadly applicable ways to explain complex phenomena or salient observations about the ecology and biogeographical distributions of plant and animal species around the world, though they have been proposed for or extended to all types of organisms. Many of these regularities of ecology and biogeography are named after the biologists who first described them.[1][2]

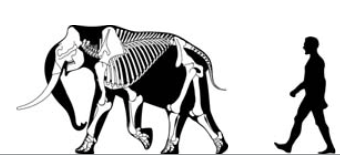

From the birth of their science, biologists have sought to explain apparent regularities in observational data. In his biology, Aristotle inferred rules governing differences between live-bearing tetrapods (in modern terms, terrestrial placental mammals). Among his rules were that brood size decreases with adult body mass, while lifespan increases with gestation period and with body mass, and fecundity decreases with lifespan. Thus, for example, elephants have smaller and fewer broods than mice, but longer lifespan and gestation.[3] Rules like these concisely organized the sum of knowledge obtained by early scientific measurements of the natural world, and could be used as models to predict future observations. Among the earliest biological rules in modern times are those of Karl Ernst von Baer (from 1828 onwards) on embryonic development (see von Baer's laws),[4] and of Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger on animal pigmentation, in 1833 (see Gloger's rule).[5] There is some scepticism among biogeographers about the usefulness of general rules. For example, J.C. Briggs, in his 1987 book Biogeography and Plate Tectonics, comments that while Willi Hennig's rules on cladistics "have generally been helpful", his progression rule is "suspect".[6]

- ^ Jørgensen, Sven Erik (2002). "Explanation of ecological rules and observation by application of ecosystem theory and ecological models". Ecological Modelling. 158 (3): 241–248. Bibcode:2002EcMod.158..241J. doi:10.1016/S0304-3800(02)00236-3.

- ^ Allee, W.C.; Schmidt, K.P. (1951). Ecological Animal Geography (2nd ed.). Joh Wiley & sons. pp. 457, 460–472.

- ^ Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury. p. 408. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lovtrupwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Glogerwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Briggs, J.C. (1987). Biogeography and Plate Tectonics. Elsevier. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-08-086851-6.