This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: use of chinese-language text needs to be pared down or edited to conform with MOS:ZH. (November 2023) |

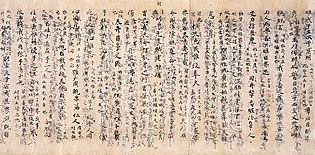

A page of an annotated Book of Documents manuscript from the 7th century, held by the Tokyo National Museum | |

| Author | Various; trad. compiled by Confucius |

|---|---|

| Original title | 書 |

| Language | Old Chinese |

| Subject | Compilation of rhetorical prose |

| Publication place | China |

The Book of Documents (Chinese: 書經; pinyin: Shūjīng; Wade–Giles: Shu King) or the Classic of History,[a] is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. It is a collection of rhetorical prose attributed to figures of ancient China, and served as the foundation of Chinese political philosophy for over two millennia.

The Book of Documents was the subject of one of China's oldest literary controversies, between proponents of different versions of the text. A version was preserved from Qin Shi Huang's burning of books and burying of scholars by scholar Fu Sheng, in 29 chapters (piān 篇). This group of texts were referred to as "Modern Script" (or "Current Script"; jīnwén 今文), because they were written with the script in use at the beginning of the Western Han dynasty.

A longer version of the Documents was said to be discovered in the wall of Confucius's family estate in Qufu by his descendant Kong Anguo in the late 2nd century BC. This new material was referred to as "Old Script" (gǔwén 古文), because they were written in the script that predated the standardization of Chinese script during the Qin. Compared to the Modern Script texts, the "Old Script" material had 16 more chapters. However, this seems to have been lost at the end of the Eastern Han dynasty, while the Modern Script text enjoyed circulation, in particular in Ouyang Gao's study, called the Ouyang Shangshu (歐陽尚書). This was the basis of studies by Ma Rong and Zheng Xuan during the Eastern Han.[2][3]

In 317 AD, Mei Ze presented to the Eastern Jin court a 58-chapter (59 if the preface is counted) Book of Documents as Kong Anguo's version of the text. This version was accepted, despite the doubts of a few scholars, and later was canonized as part of Kong Yingda's project. It was only in the 17th century that Qing dynasty scholar Yan Ruoqu demonstrated that the "old script" were actually fabrications "reconstructed" in the 3rd or 4th centuries AD.

In the transmitted edition, texts are grouped into four sections representing different eras: the legendary reign of Yu the Great, and the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties. The Zhou section accounts for over half the text. Some of its modern-script chapters are among the earliest examples of Chinese prose, recording speeches from the early years of the Zhou dynasty in the late 11th century BC. Although the other three sections purport to record earlier material, most scholars believe that even the New Script chapters in these sections were composed later than those in the Zhou section, with chapters relating to the earliest periods being as recent as the 4th or 3rd centuries BC.[4][5]

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 327–378.

- ^ 後漢書 [Book of Later Han] (in Chinese). Taipei: Dingwen shuju. 1981. p. 79.2556.

- ^ Liu Qiyu (劉起釪) (2018). 尚書學史 (in Chinese) (2nd ed.). Zhonghua shuju. p. 7.

- ^ Lewis (1999), p. 105.

- ^ Nylan (2001), pp. 134, 158.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).