The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2019) |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

Activity sectors | United States |

| Description | |

Fields of employment | Parapolice (quasi-law enforcement) |

Related jobs | Bail bondsman, thief-taker, privateer, vigilante, marshal, mercenary, citizen's arrest, neighborhood watch |

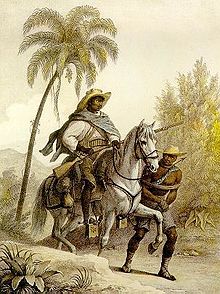

A bounty hunter is a private agent working for a bail bondsman who captures fugitives or criminals for a commission or bounty. The occupation, officially known as a bail enforcement agent or fugitive recovery agent, has traditionally operated outside the legal constraints that govern police officers and other agents of the state. This is because a bail agreement between a defendant and a bail bondsman is essentially a civil contract that is incumbent upon the bondsman to enforce. Since they are not police officers, bounty hunters are exposed to legal liabilities from which agents of the state are protected as these immunities enable police to perform their functions effectively without fear of lawsuits. Everyday citizens approached by a bounty hunter are neither required to answer their questions nor allowed to be detained. Bounty hunters are typically independent contractors paid a commission of the total bail amount that is owed by the fugitive; they provide their own professional liability insurance and only get paid if they are able to find the "skip" and bring them in.

Bounty hunting is a vestige of common law which was created during the Middle Ages. In the United States, bounty hunters primarily draw their legal imprimatur from an 1872 Supreme Court decision, Taylor v. Taintor. The practice historically existed in many parts of the world; however, as of the 21st century, it is found almost exclusively in the United States as the practice is illegal under the laws of most other countries. State laws vary widely as to the legality of the practice; Illinois, Kentucky, Oregon, and Wisconsin have outlawed commercial bail bonds, while Wyoming offers few (if any) regulations governing the practice.[1]

- ^ Adam Liptak (January 29, 2008). "Illegal Globally, Bail for Profit Remains in U.S." The New York Times.