India | |

|---|---|

| 1858–1947 | |

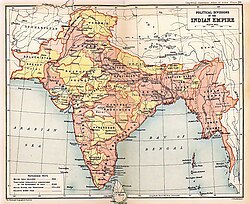

Political subdivisions of the British Raj in 1909. British India is shown in two shades of pink; Sikkim, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Princely states are shown in yellow. | |

The British Raj in relation to the British Empire in 1909 | |

| Status | Imperial political structure (comprising British India[a] and the Princely States[b][1] |

| Capital | Calcutta[2][c] (1858–1911) New Delhi (1911/1931[d]–1947) |

| Official languages | |

| Demonym(s) | Indians, British Indians |

| Government | Crown colony |

| Queen/Queen-Empress/King-Emperor | |

• 1858–1876 (Queen); 1876–1901 (Queen-Empress) | Victoria |

• 1901–1910 | Edward VII |

• 1910–1936 | George V |

• 1936 | Edward VIII |

• 1936–1947 (last) | George VI |

| Viceroy | |

• 1858–1862 (first) | Charles Canning |

• 1947 (last) | Louis Mountbatten |

| Secretary of State | |

• 1858–1859 (first) | Edward Stanley |

• 1947 (last) | William Hare |

| Legislature | Imperial Legislative Council |

| Council of State | |

| Central Legislative Assembly | |

| History | |

| 10 May 1857 | |

| 2 August 1858 | |

| 18 July 1947 | |

| took effect Midnight, 14–15 August 1947 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,993,650 km2 (1,928,060 sq mi) |

| Currency | Indian rupee |

The British Raj (/rɑːdʒ/ RAHJ; from Hindustani rāj, 'reign', 'rule' or 'government')[10] was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent,[11] lasting from 1858 to 1947.[12] It is also called Crown rule in India,[13] or Direct rule in India.[14] The region under British control was commonly called India in contemporaneous usage and included areas directly administered by the United Kingdom, which were collectively called British India, and areas ruled by indigenous rulers, but under British paramountcy, called the princely states. The region was sometimes called the Indian Empire, though not officially.[15] The area of British India contained much of the present-day states of Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar (Burma).

This system of governance was instituted on 28 June 1858, when, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the rule of the East India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria[16] (who, in 1876, was proclaimed Empress of India). It lasted until 1947, when the British Raj was partitioned into two sovereign dominion states: the Union of India (later the Republic of India) and Pakistan (later the Islamic Republic of Pakistan). Later, the People's Republic of Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan. At the inception of the Raj in 1858, Lower Burma was already a part of British India; Upper Burma was added in 1886, and the resulting union, Burma, was administered as an autonomous province until 1937, when it became a separate British colony, gaining its own independence in 1948. It was renamed Myanmar in 1989. The Chief Commissioner's Province of Aden was also part of British India at the inception of the British Raj, and became a separate colony known as Aden Colony in 1937 as well.

As India, it was a founding member of the League of Nations, and a founding member of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945.[17] India was a participating state in the Summer Olympics in 1900, 1920, 1928, 1932, and 1936.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Interpretation Act 1889 (52 & 53 Vict. c. 63), s. 18.

- ^ "Calcutta (Kalikata)", The Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. IX, Published under the Authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1908, p. 260, archived from the original on 24 May 2022, retrieved 24 May 2022,

—Capital of the Indian Empire, situated in 22° 34' N and 88° 22' E, on the east or left bank of the Hooghly river, within the Twenty-four Parganas District, Bengal

- ^ "Simla Town", The Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. XXII, Published under the Authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1908, p. 260, archived from the original on 24 May 2022, retrieved 24 May 2022,

—Head-quarters of Simla District, Punjab, and the summer capital of the Government of India, situated on a transverse spur of the Central Himālayan system system, in 31° 6' N and 77° 10' E, at a mean elevation above sea-level of 7,084 feet.

- ^ Lelyveld, David (1993). "Colonial Knowledge and the Fate of Hindustani". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 35 (4): 665–682. doi:10.1017/S0010417500018661. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179178. S2CID 144180838. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

The earlier grammars and dictionaries made it possible for the British government to replace Persian with vernacular languages at the lower levels of the judicial and revenue administration in 1837, that is, to standardize and index terminology for official use and provide for its translation to the language of the ultimate ruling authority, English. For such purposes, Hindustani was equated with Urdu, as opposed to any geographically defined dialect of Hindi and was given official status through large parts of north India. Written in the Persian script with a largely Persian and, via Persian, an Arabic vocabulary, Urdu stood at the shortest distance from the previous situation and was easily attainable by the same personnel. In the wake of this official transformation, the British government began to make its first significant efforts on behalf of vernacular education.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (2004) [1998]. "Hindi". A Dictionary of Languages: The definitive reference to more than 400 languages. A & C Black Publishers. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7136-7841-3.

In the government of northern India Persian ruled. Under the British Raj, Persian eventually declined, but, the administration remaining largely Muslim, the role of Persian was taken not by Hindi but by Urdu, known to the British as Hindustani. It was only as the Hindu majority in India began to assert itself that Hindi came into its own.

- ^ Vejdani, Farzin (2015), Making History in Iran: Education, Nationalism, and Print Culture, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 24–25, ISBN 978-0-8047-9153-3,

Although the official languages of administration in India shifted from Persian to English and Urdu in 1837, Persian continued to be taught and read there through the early twentieth century.

- ^ Everaert, Christine (2010), Tracing the Boundaries between Hindi and Urdu, Leiden and Boston: BRILL, pp. 253–254, ISBN 978-90-04-17731-4,

It was only in 1837 that Persian lost its position as official language of India to Urdu and to English in the higher levels of administration.

- ^ a b Dhir, Krishna S. (2022). The Wonder That Is Urdu. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-4301-1.

The British used the Urdu language to effect a shift from the prior emphasis on the Persian language. In 1837, the British East India Company adopted Urdu in place of Persian as the co-official language in India, along with English. In the law courts in Bengal and the North-West Provinces and Oudh (modern day Uttar Pradesh) a highly technical form of Urdu was used in the Nastaliq script, by both Muslims and Hindus. The same was the case in the government offices. In the various other regions of India, local vernaculars were used as official language in the lower courts and in government offices. ... In certain parts South Asia, Urdu was written in several scripts. Kaithi was a popular script used for both Urdu and Hindi. By 1880, Kaithi was used as court language in Bihar. However, in 1881, Hindi in Devanagari script replaced Urdu in the Nastaliq script in Bihar. In Panjab, Urdu was written in Nastaliq, Devanagari, Kaithi, and Gurumukhi.

In April 1900, the colonial government of the North-West Provinces and Oudh granted equal official status to both, Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. However, Nastaliq remained the dominant script. During the 1920s, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi deplored the controversy and the evolving divergence between Urdu and Hindi, exhorting the remerging of the two languages as Hindustani. However, Urdu continued to draw from Persian, Arabic, and Chagtai, while Hindi did the same from Sanskrit. Eventually, the controversy resulted in the loss of the official status of the Urdu language. - ^ Bayly, C. A. (1988). Indian Society and the making of the British Empire. New Cambridge History of India series. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-521-25092-7.

The use of Persian was abolished in official correspondence (1835); the government's weight was thrown behind English-medium education and Thomas Babington Macaulay's Codes of Criminal and Civil Procedure (drafted 1841–2, but not completed until the 1860s) sought to impose a rational, Western legal system on the amalgam of Muslim, Hindu and English law which had been haphazardly administered in British courts. The fruits of the Bentinck era were significant. But they were only of general importance in so far as they went with the grain of social changes which were already gathering pace in India. The Bombay and Calcutta intelligentsia were taking to English education well before the Education Minute of 1836. Flowery Persian was already giving way in north India to the fluid and demotic Urdu. As for changes in the legal system, they were only implemented after the Rebellion of 1857 when communications improved and more substantial sums of money were made available for education.

- ^

- "Raj, the". The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-860981-0.

Raj, the: British sovereignty in India before 1947 (also called, the British Raj). The word is from Hindi rāj 'reign'

- "RAJ definition and meaning". Collins Online Dictionary.

raj: (often cap; in India) rule, esp. the British rule prior to 1947

- "Raj, the". The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-860981-0.

- ^

- Hirst, Jacqueline Suthren; Zavros, John (2011), Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-44787-4, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 24 May 2022,

As the (Mughal) empire began to decline in the mid-eighteenth century, some of these regional administrations assumed a greater degree of power. Amongst these ... was the East India Company, a British trading company established by Royal Charter of Elizabeth I of England in 1600. The Company gradually expanded its influence in South Asia, in the first instance through coastal trading posts at Surat, Madras and Calcutta. (The British) expanded their influence, winning political control of Bengal and Bihar after the Battle of Plassey in 1757. From here, the Company expanded its influence dramatically across the subcontinent. By 1857, it had direct control over much of the region. The great rebellion of that year, however, demonstrated the limitations of this commercial company's ability to administer these vast territories, and in 1858 the Company was effectively nationalized, with the British Crown assuming administrative control. Hence began the period known as the British Raj, which ended in 1947 with the partition of the subcontinent into the independent nation-states of India and Pakistan.

- Salomone, Rosemary (2022), The Rise of English: Global Politics and the Power of Language, Oxford University Press, p. 236, ISBN 978-0-19-062561-0, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 24 May 2022,

Between 1858, when the British East India Company transferred power to British Crown rule (the "British Raj"), and 1947, when India gained independence, English gradually developed into the language of government and education. It allowed the Raj to maintain control by creating an elite gentry schooled in British mores, primed to participate in public life, and loyal to the Crown.

- Hirst, Jacqueline Suthren; Zavros, John (2011), Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-44787-4, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 24 May 2022,

- ^

- Vanderven, Elizabeth (2019), "National Education Systems: Asia", in Rury, John L.; Tamura, Eileen H. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Education, Oxford University Press, pp. 213–227, 222, ISBN 978-0-19-934003-3, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 24 May 2022,

During the British East India Company's domination of the Indian subcontinent (1757–1858) and the subsequent British Raj (1858–1947), it was Western-style education that came to be promoted by many as the base upon which a national and uniform education system should be built.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2014), A History of Islamic Societies (3 ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 393, ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9, retrieved 24 May 2022,

Table 14. Muslim India: outline chronology

Mughal Empire ... 1526–1858

Akbar I ... 1556–1605

Aurengzeb ... 1658–1707

British victory at Plassey ... 1757

Britain becomes paramount power ... 1818

British Raj ... 1858–1947

- Vanderven, Elizabeth (2019), "National Education Systems: Asia", in Rury, John L.; Tamura, Eileen H. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Education, Oxford University Press, pp. 213–227, 222, ISBN 978-0-19-934003-3, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 24 May 2022,

- ^

- Steinback, Susie L. (2012), Understanding the Victorians: Politics, Culture and Society in Nineteenth-Century Britain, London and New York: Routledge, p. 68, ISBN 978-0-415-77408-6, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 24 May 2022,

The rebellion was put down by the end of 1858. The British government passed the Government of India Act, and began direct Crown rule. This era was referred to as the British Raj (though in practice much remained the same).

- Ahmed, Omar (2015), Studying Indian Cinema, Auteur (now an imprint of Liverpool University Press), p. 221, ISBN 978-1-80034-738-0, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 24 May 2022,

The film opens with what is a lengthy prologue, contextualising the time and place through a detailed voice-over by Amitabh Bachchan. We are told that the year is 1893. This is significant as it was the height of the British Raj, a period of crown rule lasting from 1858 to 1947.

- Wright, Edmund (2015), A Dictionary of World History, Oxford University Press, p. 537, ISBN 978-0-19-968569-1,

More than 500 Indian kingdoms and principalities [...] existed during the 'British Raj' period (1858–1947) The rule is also called Crown rule in India

- Fair, C. Christine (2014), Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army's Way of War, Oxford University Press, p. 61, ISBN 978-0-19-989270-9,

[...] by 1909 the Government of India, reflecting on 50 years of Crown rule after the rebellion, could boast that [...]

- Steinback, Susie L. (2012), Understanding the Victorians: Politics, Culture and Society in Nineteenth-Century Britain, London and New York: Routledge, p. 68, ISBN 978-0-415-77408-6, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 24 May 2022,

- ^

- Glanville, Luke (2013), Sovereignty and the Responsibility to Protect: A New History, University of Chicago Press, p. 120, ISBN 978-0-226-07708-6, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 23 August 2020 Quote: "Mill, who was himself employed by the British East India company from the age of seventeen until the British government assumed direct rule over India in 1858."

- Pykett, Lyn (2006), Wilkie Collins, Oxford World's Classics: Authors in Context, Oxford University Press, p. 160, ISBN 978-0-19-284034-9,

In part, the Mutiny was a reaction against this upheaval of traditional Indian society. The suppression of the Mutiny after a year of fighting was followed by the break-up of the East India Company, the exile of the deposed emperor and the establishment of the British Raj, and direct rule of the Indian subcontinent by the British.

- Lowe, Lisa (2015), The Intimacies of Four Continents, Duke University Press, p. 71, ISBN 978-0-8223-7564-7,

Company rule in India lasted effectively from the Battle of Plassey in 1757 until 1858, when following the 1857 Indian Rebellion, the British Crown assumed direct colonial rule of India in the new British Raj.

- ^ Bowen, H. V.; Mancke, Elizabeth; Reid, John G. (2012), Britain's Oceanic Empire: Atlantic and Indian Ocean Worlds, C. 1550–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 106, ISBN 978-1-107-02014-6 Quote: "British India, meanwhile, was itself the powerful 'metropolis' of its own colonial empire, 'the Indian empire'."

- ^ Kaul, Chandrika. "From Empire to Independence: The British Raj in India 1858–1947". Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Mansergh, Nicholas (1974), Constitutional relations between Britain and India, London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, p. xxx, ISBN 978-0-11-580016-0, retrieved 19 September 2013 Quote: "India Executive Council: Sir Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar, Sir Firoz Khan Noon and Sir V. T. Krishnamachari served as India's delegates to the London Commonwealth Meeting, April 1945, and the U.N. San Francisco Conference on International Organisation, April–June 1945."