This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

| Bulgarian | |

|---|---|

| български език | |

| Pronunciation | bŭlgarski [ˈbɤɫɡɐrski] |

| Native to | |

| Ethnicity | Bulgarians |

| Speakers | L1: 7.6 million in Bulgaria (2011 census)[4] L1 + L2: 7.9 million in all countries (2023)[5] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Institute for Bulgarian Language, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | bg |

| ISO 639-2 | bul |

| ISO 639-3 | bul |

| Glottolog | bulg1262 |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-hb < 53-AAA-h |

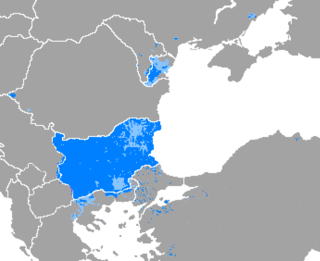

The Bulgarian-speaking world:[image reference needed] regions where Bulgarian is the language of the majority regions where Bulgarian is the language of a significant minority | |

Bulgarian (/bʌlˈɡɛəriən/ , /bʊlˈ-/ bu(u)l-GAIR-ee-ən; български език, bŭlgarski ezik, pronounced [ˈbɤɫɡɐrski] ) is an Eastern South Slavic language spoken in Southeast Europe, primarily in Bulgaria. It is the language of the Bulgarians.

Along with the closely related Macedonian language (collectively forming the East South Slavic languages), it is a member of the Balkan sprachbund and South Slavic dialect continuum of the Indo-European language family. The two languages have several characteristics that set them apart from all other Slavic languages, including the elimination of case declension, the development of a suffixed definite article, and the lack of a verb infinitive. They retain and have further developed the Proto-Slavic verb system (albeit analytically). One such major development is the innovation of evidential verb forms to encode for the source of information: witnessed, inferred, or reported.

It is the official language of Bulgaria, and since 2007 has been among the official languages of the European Union.[13][14] It is also spoken by the Bulgarian historical communities in North Macedonia, Ukraine, Moldova, Serbia, Romania, Hungary, Albania and Greece.

- ^ Loring M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, 1995, Princeton University Press, p.65 , ISBN 0-691-04356-6

- ^ Djokić, Dejan (2003). Yugoslavism: Histories of a Failed Idea, 1918-1992. Hurst. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-85065-663-0.

With such policies the new Yugoslav authorities largely overcame the residual pro-Bulgarian feeling among much of the population, and survived the split with Bulgaria in 1948. Pro-Bulgarians among Macedonians suffered severe repression as а result. However, while occasional trial continued throughout the life of Communist Yugoslavia, the vast bulk took place in the late 1940s. The new authorities were successful in building а distinct national coпsciousness based on the available differences between Macedoпia and Bulgaria proper, апd bу the time Yugoslavia collapsed in the early 1990s, those who continued to look to Bulgaria were very few indeed.18 The change from the pre-war situatioп of unrecognised minority status and attempted assimilation by Serbia to one where the Macedonians were the majority people in their own republic with consideraЫe autonomy within Yнgoslavia's federation/con-federation had obvious attractions...

18 However, in Macedonia today remain those who identify as Bulgariaпs. Hostility to them reшaiпs, even if less than in Communist Yugoslavia, where it was forbidden to proclaim Bulgarian identity, with the partial exception of the Strumica regioп where the popнlation was allowed more leeway and where most of the 3,000-4,000 Bulgarians in Macedonia in the censнses appearcd. Examples of the coпtinuing hostility are: thc Supreme Court iп January 1994 banпed the pro-Bulgarian Нumап Rights Party led by Ilija Ilijevski and the refused registration of aпother pro-Bulgariaп group in Ohrid and other harassment. - ^ "Bulgarians in Albania". Omda.bg. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

2011Censuswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bulgarian language at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- ^ "Národnostní menšiny v České republice a jejich jazyky" [National Minorities in Czech Republic and Their Language] (PDF) (in Czech). Government of Czech Republic. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014.

Podle čl. 3 odst. 2 Statutu Rady je jejich počet 12 a jsou uživateli těchto menšinových jazyků: ..., srbština a ukrajinština

- ^ "Implementation of the Charter in Hungary". Database for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Public Foundation for European Comparative Minority Research. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Frawley, William (2003). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-19-513977-8.

- ^ Bayır, Derya (2013). Minorities and nationalism in Turkish law. Cultural Diversity and Law. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 88, 203–204. ISBN 978-1-4094-7254-4.

- ^ Toktaş, Şule; Araş, Bulent (2009). "The EU and Minority Rights in Turkey". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (4): 697–720. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2009.tb00664.x. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 25655744.

- ^ Köksal, Yonca (2006). "Minority Policies in Bulgaria and Turkey: The Struggle to Define a Nation". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 6 (4): 501–521. doi:10.1080/14683850601016390. ISSN 1468-3857. S2CID 153761516.

- ^ Özlem, Kader (2019). "An Evaluation on Istanbul's Bulgarians as the "Invisible Minority" of Turkey". Turan-Sam. 11 (43): 387–393. ISSN 1308-8041.

- ^ EUR-Lex (12 December 2006). "Council Regulation (EC) No 1791/2006 of 20 November 2006". Official Journal of the European Union. Europa web portal. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ "Languages in Europe – Official EU Languages". EUROPA web portal. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2009.