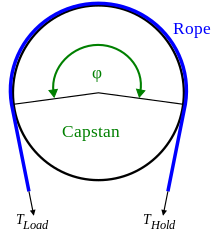

The capstan equation[1] or belt friction equation, also known as Euler–Eytelwein formula[2] (after Leonhard Euler and Johann Albert Eytelwein),[3] relates the hold-force to the load-force if a flexible line is wound around a cylinder (a bollard, a winch or a capstan).[4][1]

It also applies for fractions of one turn as occur with rope drives or band brakes.

Because of the interaction of frictional forces and tension, the tension on a line wrapped around a capstan may be different on either side of the capstan. A small holding force exerted on one side can carry a much larger loading force on the other side; this is the principle by which a capstan-type device operates.

A holding capstan is a ratchet device that can turn only in one direction; once a load is pulled into place in that direction, it can be held with a much smaller force. A powered capstan, also called a winch, rotates so that the applied tension is multiplied by the friction between rope and capstan. On a tall ship a holding capstan and a powered capstan are used in tandem so that a small force can be used to raise a heavy sail and then the rope can be easily removed from the powered capstan and tied off.

In rock climbing this effect allows a lighter person to hold (belay) a heavier person when top-roping, and also produces rope drag during lead climbing.

The formula is

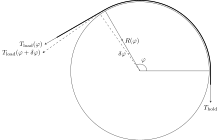

where is the applied tension on the line, is the resulting force exerted at the other side of the capstan, is the coefficient of friction between the rope and capstan materials, and is the total angle swept by all turns of the rope, measured in radians (i.e., with one full turn the angle ).

For dynamic applications such as belt drives or brakes the quantity of interest is the force difference between and . The formula for this is

Several assumptions must be true for the equations to be valid:

- The rope is on the verge of full sliding, i.e. is the maximum load that one can hold. Smaller loads can be held as well, resulting in a smaller effective contact angle .

- It is important that the line is not rigid, in which case significant force would be lost in the bending of the line tightly around the cylinder. (The equation must be modified for this case.) For instance a Bowden cable is to some extent rigid and doesn't obey the principles of the capstan equation.

- The line is non-elastic.

It can be observed that the force gain increases exponentially with the coefficient of friction, the number of turns around the cylinder, and the angle of contact. Note that the radius of the cylinder has no influence on the force gain.

The table below lists values of the factor based on the number of turns and coefficient of friction μ.

| Number of turns |

Coefficient of friction μ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |

| 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 9 |

| 1 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 6.6 | 12 | 23 | 43 | 81 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 12 | 43 | 152 | 535 | 1881 | 6661 |

| 3 | 6.6 | 43 | 286 | 1881 | 12392 | 81612 | 537503 |

| 4 | 12 | 152 | 1881 | 23228 | 286751 | 3540026 | 43702631 |

| 5 | 23 | 535 | 12392 | 286751 | 6635624 | 153552935 | 3553321281 |

From the table it is evident why one seldom sees a sheet (a rope to the loose side of a sail) wound more than three turns around a winch. The force gain would be extreme besides being counter-productive since there is risk of a riding turn, result being that the sheet will foul, form a knot and not run out when eased (by slacking grip on the tail (free end)).

It is both ancient and modern practice for anchor capstans and jib winches to be slightly flared out at the base, rather than cylindrical, to prevent the rope (anchor warp or sail sheet) from sliding down. The rope wound several times around the winch can slip upwards gradually, with little risk of a riding turn, provided it is tailed (loose end is pulled clear), by hand or a self-tailer.

For instance, the factor "153,552,935" (5 turns around a capstan with a coefficient of friction of 0.6) means, in theory, that a newborn baby would be capable of holding (not moving) the weight of two USS Nimitz supercarriers (97,000 tons each, but for the baby it would be only a little more than 1 kg). The large number of turns around the capstan combined with such a high friction coefficient mean that very little additional force is necessary to hold such heavy weight in place. The cables necessary to support this weight, as well as the capstan's ability to withstand the crushing force of those cables, are separate considerations.

- ^ a b Attaway, Stephen W. (1999-11-01). The Mechanics of Friction in Rope Rescue. International Tech Rescue Symposium. Retrieved 23 Nov 2022.

- ^ Metzger, Andreas; Konyukhov, Alexander; Schweizerhof, Karl (2011). "Finite Element implementation for the EULER–EYTELWEIN problem and further use in FEM-simulation of common nautical knots". PAMM Proc. Appl. Math. Mech. 11: 249–250. doi:10.1002/pamm.201110116. S2CID 119597604.

- ^ Mann, Herman (5 May 2005). "Belt Friction". Archived from the original on 2007-08-02. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ Johnson, K. L. (1985). Contact Mechanics (PDF). Retrieved February 14, 2011.