| Capture of Columbia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Campaign of the Carolinas | |||||||

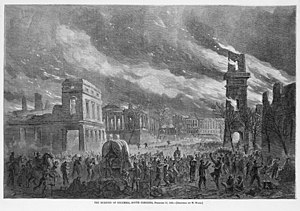

The Burning of Columbia, South Carolina, on February 17, 1865, as depicted in Harper's Weekly | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 60,000 | ~500 | ||||||

The capture of Columbia occurred February 17–18, 1865, during the Carolinas Campaign of the American Civil War. The state capital of Columbia, South Carolina, was captured by Union forces under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. Much of the city was burned, although it is not clear which side caused the fires.

After Gen. Sherman's March to the Sea captured Savannah, Georgia, he turned his forces north and marched into the Carolinas. Splitting his forces to deceive the Confederates, Sherman maneuvered towards Columbia in early February 1865. Columbia was of considerable strategic importance: it was a center of manufacturing, a rail hub, a state capital, and a symbolic origin point of the secession movement. Poor planning and leadership on the part of the Confederates meant that Columbia was underdefended. Confederate forces, under P. G. T. Beauregard, had been spread thin rather than concentrated to take Sherman in field combat. No preparations had been made for the evacuation of the city's citizens, army materiel, or administrative functions (including the Confederate treasury's printing presses).

When it became apparent in mid February that the full might of the Union army was bearing down on Columbia, the city erupted into panic. Hasty last minute attempts were made to evacuate the city's military supplies, but almost none were salvaged. The city's considerable cotton reserves were ordered taken into the streets to be burned so that they could not fall into the hands of the enemy. Retreating and demoralized Confederate elements began to stream into the city, precipitating riots. The city fell into disorder, and martial law was declared on the 16th. Realizing the city was lost, Confederate forces withdrew from the city overnight. Fires broke out in the street cotton during the night, due either to drunk Confederates, Union shelling, or both.

The Union Army entered the city on the morning of the 17th. Union forces set about garrisoning the city with a provost guard, and extinguishing numerous fires that were already burning. Despite efforts by Union commanders, drunkenness began to spread through the army. Fires also continued to burn throughout the city; at least nine separate groups of fires were extinguished during the day. As evening approached, the situation was becoming dire. A new garrison was called into the city, but when it entered around 8 pm, they found a new fire had started. This final fire was the most destructive. Driven by high winds, it could not be extinguished even by the thousands of troops in the provost guard. Undisciplined Union soldiers complicated firefighting efforts, as rogue elements of the army were generally looting the city, and some were setting fires. Finally, winds died down around 2 am on the 18th, and the Union army was able to extinguish the fire. Further garrison elements were also called into the city, which restored order by 5 am.

A third of the city's buildings were destroyed in the various fires. The responsibility for the fires has been a topic of historical, and popular, debate. The idea that Gen. Sherman ordered the burning of Columbia has persisted as part of the myth of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. But modern historians have concluded that no one cause led to the burning of Columbia, and that Sherman did not order the burning. Rather, the chaotic atmosphere in the city on the occasion of its fall led to the ideal conditions for a fire to start and spread.

- ^ "The Capture of Columbia". The History Engine. University of Richmond. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2020.