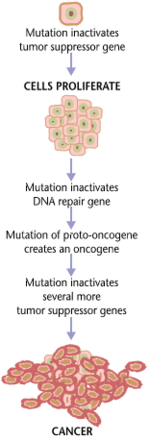

Carcinogenesis, also called oncogenesis or tumorigenesis, is the formation of a cancer, whereby normal cells are transformed into cancer cells. The process is characterized by changes at the cellular, genetic, and epigenetic levels and abnormal cell division. Cell division is a physiological process that occurs in almost all tissues and under a variety of circumstances. Normally, the balance between proliferation and programmed cell death, in the form of apoptosis, is maintained to ensure the integrity of tissues and organs. According to the prevailing accepted theory of carcinogenesis, the somatic mutation theory, mutations in DNA and epimutations that lead to cancer disrupt these orderly processes by interfering with the programming regulating the processes, upsetting the normal balance between proliferation and cell death.[1][2][3][4][5] This results in uncontrolled cell division and the evolution of those cells by natural selection in the body. Only certain mutations lead to cancer whereas the majority of mutations do not.[citation needed]

Variants of inherited genes may predispose individuals to cancer. In addition, environmental factors such as carcinogens and radiation cause mutations that may contribute to the development of cancer. Finally random mistakes in normal DNA replication may result in cancer-causing mutations.[6] A series of several mutations to certain classes of genes is usually required before a normal cell will transform into a cancer cell.[7][8][9][10][11] Recent comprehensive patient-level classification and quantification of driver events in TCGA cohorts revealed that there are on average 12 driver events per tumor, of which 0.6 are point mutations in oncogenes, 1.5 are amplifications of oncogenes, 1.2 are point mutations in tumor suppressors, 2.1 are deletions of tumor suppressors, 1.5 are driver chromosome losses, 1 is a driver chromosome gain, 2 are driver chromosome arm losses, and 1.5 are driver chromosome arm gains.[12] Mutations in genes that regulate cell division, apoptosis (cell death), and DNA repair may result in uncontrolled cell proliferation and cancer.

Cancer is fundamentally a disease of regulation of tissue growth. In order for a normal cell to transform into a cancer cell, genes that regulate cell growth and differentiation must be altered.[13] Genetic and epigenetic changes can occur at many levels, from gain or loss of entire chromosomes, to a mutation affecting a single DNA nucleotide, or to silencing or activating a microRNA that controls expression of 100 to 500 genes.[14][15] There are two broad categories of genes that are affected by these changes. Oncogenes may be normal genes that are expressed at inappropriately high levels, or altered genes that have novel properties. In either case, expression of these genes promotes the malignant phenotype of cancer cells. Tumor suppressor genes are genes that inhibit cell division, survival, or other properties of cancer cells. Tumor suppressor genes are often disabled by cancer-promoting genetic changes. Finally Oncovirinae, viruses that contain an oncogene, are categorized as oncogenic because they trigger the growth of tumorous tissues in the host. This process is also referred to as viral transformation.It is also believed that cancer is caused due to chromosomal abnormalities as explained in chromosome theory of cancer.[16]

- ^ Majérus, Marie-Ange (1 July 2022). "The cause of cancer: The unifying theory". Advances in Cancer Biology - Metastasis. 4: 100034. doi:10.1016/j.adcanc.2022.100034. ISSN 2667-3940. S2CID 247145082.

- ^ Nowell, Peter C. (1 October 1976). "The Clonal Evolution of Tumor Cell Populations: Acquired genetic lability permits stepwise selection of variant sublines and underlies tumor progression". Science. 194 (4260): 23–28. Bibcode:1976Sci...194...23N. doi:10.1126/science.959840. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 959840. S2CID 38445059.

- ^ Hanahan, Douglas; Weinberg, Robert A (7 January 2000). "The Hallmarks of Cancer". Cell. 100 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 10647931. S2CID 1478778.

- ^ Hahn, William C.; Weinberg, Robert A. (14 November 2002). "Rules for Making Human Tumor Cells". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (20): 1593–1603. doi:10.1056/NEJMra021902. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 12432047.

- ^ Calkins, Gary N. (11 December 1914). "Zur Frage der Entstehung maligner Tumoren . By Th. Boveri. Jena, Gustav Fischer. 1914. 64 pages". Science. 40 (1041): 857–859. doi:10.1126/science.40.1041.857. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Tomasetti C, Li L, Vogelstein B (23 March 2017). "Stem cell divisions, somatic mutations, cancer etiology, and cancer prevention". Science. 355 (6331): 1330–1334. Bibcode:2017Sci...355.1330T. doi:10.1126/science.aaf9011. PMC 5852673. PMID 28336671.

- ^ Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjöblom T, Leary RJ, et al. (November 2007). "The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers". Science. 318 (5853): 1108–13. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1108W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.218.5477. doi:10.1126/science.1145720. PMID 17932254. S2CID 7586573.

- ^ Knudson AG (November 2001). "Two genetic hits (more or less) to cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 1 (2): 157–62. doi:10.1038/35101031. PMID 11905807. S2CID 20201610.

- ^ Fearon ER, Vogelstein B (June 1990). "A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis". Cell. 61 (5): 759–67. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-I. PMID 2188735. S2CID 22975880.

- ^ Belikov AV (September 2017). "The number of key carcinogenic events can be predicted from cancer incidence". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 12170. Bibcode:2017NatSR...712170B. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12448-7. PMC 5610194. PMID 28939880.

- ^ Belikov AV, Vyatkin A, Leonov SV (6 August 2021). "The Erlang distribution approximates the age distribution of incidence of childhood and young adulthood cancers". PeerJ. 9: e11976. doi:10.7717/peerj.11976. PMC 8351573. PMID 34434669.

- ^ Vyatkin, Alexey D.; Otnyukov, Danila V.; Leonov, Sergey V.; Belikov, Aleksey V. (14 January 2022). "Comprehensive patient-level classification and quantification of driver events in TCGA PanCanAtlas cohorts". PLOS Genetics. 18 (1): e1009996. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1009996. PMC 8759692. PMID 35030162.

- ^ Croce CM (January 2008). "Oncogenes and cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (5): 502–11. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072367. PMID 18234754.

- ^ Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM (February 2005). "Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs". Nature. 433 (7027): 769–73. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..769L. doi:10.1038/nature03315. PMID 15685193. S2CID 4430576.

- ^ Balaguer F, Link A, Lozano JJ, Cuatrecasas M, Nagasaka T, Boland CR, Goel A (August 2010). "Epigenetic silencing of miR-137 is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis". Cancer Research. 70 (16): 6609–18. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0622. PMC 2922409. PMID 20682795.

- ^ "How Chromosome Imbalances Can Drive Cancer | Harvard Medical School". hms.harvard.edu. 6 July 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.