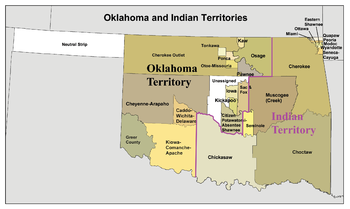

The Cherokee Commission, (also known as the Jerome Commission) was a three-person bi-partisan body created by 23rd President Benjamin Harrison (1833–1901, served 1889–1893), to operate under the direction of the United States Secretary of the Interior, of the President's Cabinet, as empowered by Section 14 of the Indian Appropriations Act of March 2, 1889, passed by the United States Congress and signed by President Harrison. Section 15 of the same Act empowered the President of the United States to open land for settlement. The Commission's purpose was to legally acquire land already occupied by the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in the new Oklahoma Territory for non-indigenous homestead acreage.

Eleven agreements involving nineteen different tribes were signed over during the period of May 1890 through November 1892. The tribes resisted and protested land cession. Not all of the residents understood the terms of the agreements. The Commission tried to dissuade tribes from retaining the services of outside law attorneys. Not all language interpreters were literate. Agreement terms varied by tribe. As negotiations with the Cherokee Nation snagged, the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Territories recommended bypassing further negotiations and annexing outright the land segment of the Cherokee Outlet.

The Commission continued to function until August 1893. Additional lawsuits, further U.S. Supreme Court rulings, further investigations and mandated compensation for irregularities ensued for another 110 years of controversy through the end of the 20th century. The U.S. Congress failed to respond to a legal protest from the Tonkawa tribe, or to an Indian Rights Association investigation that condemned the Jerome Commission / Cherokee Commission's actions with the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples. Commission attempts to negotiate signed agreements produced no results with the Osage, Kaw, Otoe and Ponca groups.

The 1887 Dawes Act[1] empowered the President of the United States to survey commonly held tribal lands and allot the land to individual tribal members, with the individual land patents to be held in trust as non-taxable by the federal government for 25 years.

- ^ Johansen, Pritzker (2007) p. 278