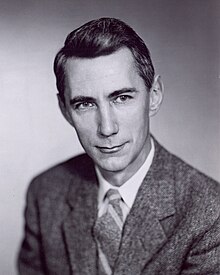

Claude Elwood Shannon (April 30, 1916 – February 24, 2001) was an American mathematician, electrical engineer, computer scientist, cryptographer and inventor known as the "father of information theory" and as the "father of the Information Age".[1] Shannon was the first to describe the Boolean gates (electronic circuits) that are essential to all digital electronic circuits, and was one of the founding fathers of artificial intelligence.[2][3][4][1] Shannon is credited with laying the foundations of the Information Age.[5][6][7]

At the University of Michigan, Shannon dual degreed, graduating with a Bachelor of Science in both electrical engineering and mathematics in 1936. A 21-year-old master's degree student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in electrical engineering, his thesis concerned switching circuit theory, demonstrating that electrical applications of Boolean algebra could construct any logical numerical relationship,[8] thereby establishing the theory behind digital computing and digital circuits.[9] The thesis has been claimed to be the most important master's thesis of all time,[8] as in 1985, Howard Gardner described it as "possibly the most important, and also the most famous, master's thesis of the century",[10] while Herman Goldstine described it as "surely ... one of the most important master's theses ever written ... It helped to change digital circuit design from an art to a science."[11] It has also been called the "birth certificate of the digital revolution",[12] and it won the 1939 Alfred Noble Prize.[13] Shannon then graduated with a PhD in mathematics from MIT in 1940,[14] with his thesis focused on genetics, with it deriving important results, but it went unpublished.[15]

Shannon contributed to the field of cryptanalysis for national defense of the United States during World War II, including his fundamental work on codebreaking and secure telecommunications, writing a paper which is considered one of the foundational pieces of modern cryptography,[16] with his work described as "a turning point, and marked the closure of classical cryptography and the beginning of modern cryptography."[17] The work of Shannon is the foundation of secret-key cryptography, including the work of Horst Feistel, the Data Encryption Standard (DES), Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), and more.[17] As a result, Shannon has been called the "founding father of modern cryptography".[18]

His mathematical theory of communication laid the foundations for the field of information theory,[19][14] with his famous paper being called the "Magna Carta of the Information Age" by Scientific American,[6][20] along with his work being described as being at "the heart of today's digital information technology".[21] Robert G. Gallager referred to the paper as a "blueprint for the digital era".[22] Regarding the influence that Shannon had on the digital age, Solomon W. Golomb remarked "It's like saying how much influence the inventor of the alphabet has had on literature."[19] Shannon's theory is widely used and has been fundamental to the success of many scientific endeavors, such as the invention of the compact disc, the development of the Internet, feasibility of mobile phones, the understanding of black holes, and more, and is at the intersection of numerous important fields.[23][24] Shannon also formally introduced the term "bit".[25][7]

Shannon made numerous contributions to the field of artificial intelligence,[2] writing papers on programming a computer for chess, which have been immensely influential.[26][27] His Theseus machine was the first electrical device to learn by trial and error, being one of the first examples of artificial intelligence.[28][29] He also co-organized and participated in the Dartmouth workshop of 1956, considered the founding event of the field of artificial intelligence.[30][31]

Rodney Brooks declared that Shannon was the 20th century engineer who contributed the most to 21st century technologies,[28] and Solomon W. Golomb described the intellectual achievement of Shannon as "one of the greatest of the twentieth century".[32] His achievements are considered to be on par with those of Albert Einstein, Sir Isaac Newton, and Charles Darwin.[5][19][4][33]

- ^ a b Roberts, Siobhan (April 30, 2016). "The Forgotten Father of the Information Age". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Slater, Robert (1989). Portraits in Silicon. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Pr. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-262-69131-4.

- ^ James, Ioan (2009). "Claude Elwood Shannon 30 April 1916 – 24 February 2001". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 55: 257–265. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2009.0015.

- ^ a b Horgan, John (April 27, 2016). "Claude Shannon: Tinkerer, Prankster, and Father of Information Theory". IEEE. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Atmar, Wirt (2001). "A Profoundly Repeated Pattern". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 82 (3): 208–211. ISSN 0012-9623. JSTOR 20168572.

- ^ a b Goodman, Jimmy Soni and Rob (July 30, 2017). "Claude Shannon: The Juggling Poet Who Gave Us the Information Age". The Daily Beast. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Tse, David (December 22, 2020). "How Claude Shannon Invented the Future". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Poundstone, William (2005). Fortune's Formula : The Untold Story of the Scientific Betting System That Beat the Casinos and Wall Street. Hill & Wang. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8090-4599-0.

- ^ Chow, Rony (June 5, 2021). "Claude Shannon: The Father of Information Theory". History of Data Science. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Gardner, Howard (1985). The Mind's New Science: A History of the Cognitive Revolution. Basic Books. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-465-04635-5.

- ^ Goldstine, Herman H. (1972). The Computer from Pascal to von Neumann (PDF). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-0-691-08104-5.

- ^ Vignes, Alain (2023). Silicon, From Sand to Chips, 1: Microelectronic Components. Hoboken: ISTE Ltd / John Wiley and Sons Inc. pp. xv. ISBN 978-1-78630-921-1.

- ^ Rioul, Olivier (2021), Duplantier, Bertrand; Rivasseau, Vincent (eds.), "This is IT: A Primer on Shannon's Entropy and Information", Information Theory: Poincaré Seminar 2018, Progress in Mathematical Physics, vol. 78, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 49–86, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-81480-9_2, ISBN 978-3-030-81480-9, retrieved July 28, 2024

- ^ a b "Claude E. Shannon | IEEE Information Theory Society". www.itsoc.org. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:11was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Shimeall, Timothy J.; Spring, Jonathan M. (2013). Introduction to Information Security: A Strategic-Based Approach. Syngress. p. 167. ISBN 978-1597499699.

- ^ a b Koç, Çetin Kaya; Özdemir, Funda (2023). "Development of Cryptography since Shannon" (PDF). Handbook of Formal Analysis and Verification in Cryptography: 1–56. doi:10.1201/9781003090052-1. ISBN 978-1-003-09005-2.

- ^ Bruen, Aiden A.; Forcinito, Mario (2005). Cryptography, Information Theory, and Error-Correction: A Handbook for the 21st Century. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Interscience. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-471-65317-2. OCLC 56191935.

- ^ a b c Poundstone, William (2005). Fortune's Formula : The Untold Story of the Scientific Betting System That Beat the Casinos and Wall Street. Hill & Wang. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-8090-4599-0.

- ^ Goodman, Rob; Soni, Jimmy (2018). "Genius in Training". Alumni Association of the University of Michigan. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ Guizzo, Erico Marui (2003). The Essential Message: Claude Shannon and the Making of Information Theory (Master's thesis). University of Sao Paulo. hdl:1721.1/39429. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Claude Shannon: Reluctant Father of the Digital Age". MIT Technology Review. July 1, 2001. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Chang, Mark (2014). Principles of Scientific Methods. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-4822-3809-9.

- ^ Jha, Alok (April 30, 2016). "Without Claude Shannon's information theory there would have been no internet". The Guardian. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ Keats, Jonathon (November 11, 2010). Virtual Words: Language from the Edge of Science and Technology. Oxford University Press. p. 36. doi:10.1093/oso/9780195398540.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-539854-0.

- ^ Apter, Michael J. (2018). The Computer Simulation of Behaviour. Routledge Library Editions: Artificial intelligence. London New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8153-8566-0.

- ^ Lowood, Henry; Guins, Raiford, eds. (June 3, 2016). Debugging Game History: A Critical Lexicon. The MIT Press. pp. 31–32. doi:10.7551/mitpress/10087.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-262-33194-4.

- ^ a b Brooks, Rodney (January 25, 2022). "How Claude Shannon Helped Kick-start Machine Learning". ieeespectrum. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

MITwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ McCarthy, John; Minsky, Marvin L.; Rochester, Nathaniel; Shannon, Claude E. (December 15, 2006). "A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, August 31, 1955". AI Magazine. 27 (4): 12. doi:10.1609/aimag.v27i4.1904. ISSN 2371-9621.

- ^ Solomonoff, Grace (May 6, 2023). "The Meeting of the Minds That Launched AI". ieeespectrum. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Golomb, Solomon W. (January 2002). "Claude Elwood Shannon (1916–2001)" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 49 (1).

- ^ Rutledge, Tom (August 16, 2017). "The Man Who Invented Information Theory". Boston Review. Retrieved October 31, 2023.