| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Anafranil, Clomicalm, others |

| Other names | Clomipramine; 3-Chloroimipramine; G-34586[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697002 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous[2] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~50%[4] |

| Protein binding | 96–98%[4] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2D6)[4] |

| Metabolites | Desmethylclomipramine[4] |

| Elimination half-life | CMI: 19–37 hours[4] DCMI: 54–77 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Renal (51–60%)[4] Feces (24–32%)[4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.587 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

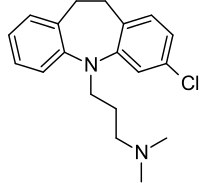

| Formula | C19H23ClN2 |

| Molar mass | 314.86 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Clomipramine, sold under the brand name Anafranil among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA).[5] It is used in the treatment of various conditions, most notably obsessive–compulsive disorder but also many other disorders, including hyperacusis, panic disorder, major depressive disorder, trichotillomania,[6] body dysmorphic disorder[7][8][9] and chronic pain.[5] It has also been notably used to treat premature ejaculation[5] and the cataplexy associated with narcolepsy.[10][11]

It may also address certain fundamental features surrounding narcolepsy besides cataplexy (especially hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations).[12] The evidence behind this, however, is less robust.

As with other antidepressants (notably including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), it may paradoxically increase the risk of suicide in those under the age of 25, at least in the first few weeks of treatment.[5]

It is typically taken by mouth, although intravenous preparations are sometimes used.[13][14]

Common side effects include dry mouth, constipation, loss of appetite, sleepiness, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and trouble urinating.[5] Serious side effects include an increased risk of suicidal behavior in those under the age of 25, seizures, mania, and liver problems.[5] If stopped suddenly, a withdrawal syndrome may occur with headaches, sweating, and dizziness.[5] It is unclear if it is safe for use in pregnancy.[5] Its mechanism of action is not entirely clear but is believed to involve increased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine.[5]

Clomipramine was discovered in 1964 by the Swiss drug manufacturer Ciba-Geigy.[15] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[16] It is available as a generic medication.[5]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Elks2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Taylor D, Paton C, Shitij K (2012). Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry (11th ed.). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cite error: The named reference

LemkeWilliams2012was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Clomipramine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ Swedo, S E et al. "A double-blind comparison of clomipramine and desipramine in the treatment of trichotillomania (hair pulling)." The New England Journal of Medicine Vol. 321,8 (1989): 497-501. doi:10.1056/NEJM198908243210803

- ^ Adebayo, Kazeem Olaide et al. "Body dysmorphic disorder in a Nigerian boy presenting as depression: a case report and literature review." International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine Vol. 44,4 (2012): 367-72. doi:10.2190/PM.44.4.f

- ^ Phillips, K.A., Albertini, R.S., Siniscalchi, J.M., Khan, A. and Robinson, M., 2001. "Effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for body dysmorphic disorder: a chart-review study." Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(9), pp. 721-727.

- ^ Pallanti, S. and Koran, L.M., 1996. "Intravenous, pulse-loaded clomipramine in body dysmorphic disorder: two case reports." CNS Spectrums, 1(2), pp. 54-57.

- ^ Shapiro, W. R. (1975). "Treatment of cataplexy with clomipramine." Archives of Neurology, 32(10), pp. 653-656.

- ^ Dauvilliers Y, Siegel JM, Lopez R, Torontali ZA, Peever JH. "Cataplexy—clinical aspects, pathophysiology and management strategy." Nature Reviews Neurology. 2014 Jul, 10(7):386-95..

- ^ Chen C. N. (1980). "The use of clomipramine as an REM sleep suppressant in narcolepsy." Postgraduate Medical Journal, 56 Suppl 1, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Karameh, Wael Karameh, and Munir Khani. "Intravenous Clomipramine for Treatment-Resistant Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder." The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology Vol. 19,2 pyv084. 28 July 2015, doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyv084

- ^ Sallee, F R et al. "Pulse intravenous clomipramine for depressed adolescents: double-blind, controlled trial." The American Journal of Psychiatry Vol. 154,5 (1997): 668-73. doi:10.1176/ajp.154.5.668

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Zohar2012was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.