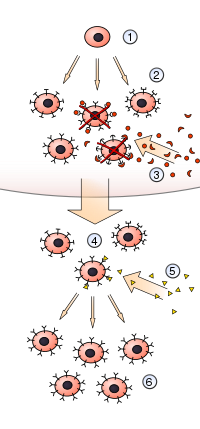

1) A hematopoietic stem cell undergoes differentiation and genetic rearrangement to produce

2) immature lymphocytes with many different antigen receptors. Those that bind to

3) antigens from the body's own tissues are destroyed, while the rest mature into

4) inactive lymphocytes. Most of these never encounter a matching

5) foreign antigen, but those that do are activated and produce

6) many clones of themselves.

In immunology, clonal selection theory explains the functions of cells of the immune system (lymphocytes) in response to specific antigens invading the body. The concept was introduced by Australian doctor Frank Macfarlane Burnet in 1957, in an attempt to explain the great diversity of antibodies formed during initiation of the immune response.[1][2] The theory has become the widely accepted model for how the human immune system responds to infection and how certain types of B and T lymphocytes are selected for destruction of specific antigens.[3]

The theory states that in a pre-existing group of lymphocytes (both B and T cells), a specific antigen activates (i.e. selects) only its counter-specific cell, which then induces that particular cell to multiply, producing identical clones for antibody production. This activation occurs in secondary lymphoid organs such as the spleen and the lymph nodes.[4] In short, the theory is an explanation of the mechanism for the generation of diversity of antibody specificity.[5] The first experimental evidence came in 1958, when Gustav Nossal and Joshua Lederberg showed that one B cell always produces only one antibody.[6] The idea turned out to be the foundation of molecular immunology, especially in adaptive immunity.[7]

- ^ Burnet, FM (1976). "A modification of Jerne's theory of antibody production using the concept of clonal selection". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 26 (2): 119–21. doi:10.3322/canjclin.26.2.119. PMID 816431. S2CID 40609269.

- ^ Cohn, Melvin; Av Mitchison, N.; Paul, William E.; Silverstein, Arthur M.; Talmage, David W.; Weigert, Martin (2007). "Reflections on the clonal-selection theory". Nature Reviews Immunology. 7 (10): 823–830. doi:10.1038/nri2177. PMID 17893695. S2CID 24741671.

- ^ Rajewsky, Klaus (1996). "Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system". Nature. 381 (6585): 751–758. Bibcode:1996Natur.381..751R. doi:10.1038/381751a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 8657279. S2CID 4279640.

- ^ Murphy, Kenneth (2012). Janeway's Immunobiology 8th Edition. New York, NY: Garland Science. ISBN 9780815342434.

- ^ Jordan, Margaret A; Baxter, Alan G (2007). "Quantitative and qualitative approaches to GOD: the first 10 years of the clonal selection theory". Immunology and Cell Biology. 86 (1): 72–79. doi:10.1038/sj.icb.7100140. PMID 18040281. S2CID 19122290.

- ^ Nossal, G. J. V.; Lederberg, Joshua (1958). "Antibody Production by Single Cells". Nature. 181 (4620): 1419–1420. Bibcode:1958Natur.181.1419N. doi:10.1038/1811419a0. PMC 2082245. PMID 13552693.

- ^ Medzhitov, R. (2013). "Pattern Recognition Theory and the Launch of Modern Innate Immunity". The Journal of Immunology. 191 (9): 4473–4474. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1302427. PMID 24141853.