Cold fusion is a hypothesized type of nuclear reaction that would occur at, or near, room temperature. It would contrast starkly with the "hot" fusion that is known to take place naturally within stars and artificially in hydrogen bombs and prototype fusion reactors under immense pressure and at temperatures of millions of degrees, and be distinguished from muon-catalyzed fusion. There is currently no accepted theoretical model that would allow cold fusion to occur.

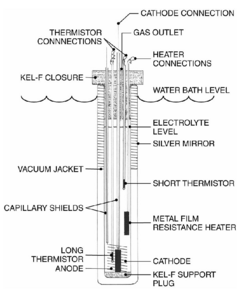

In 1989, two electrochemists at the University of Utah, Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons, reported that their apparatus had produced anomalous heat ("excess heat") of a magnitude they asserted would defy explanation except in terms of nuclear processes.[1] They further reported measuring small amounts of nuclear reaction byproducts, including neutrons and tritium.[2] The small tabletop experiment involved electrolysis of heavy water on the surface of a palladium (Pd) electrode.[3] The reported results received wide media attention[3] and raised hopes of a cheap and abundant source of energy.[4]

Many scientists tried to replicate the experiment with the few details available. Expectations diminished as a result of numerous failed replications, the retraction of several previously reported positive replications, the identification of methodological flaws and experimental errors in the original study, and, ultimately, the confirmation that Fleischmann and Pons had not observed the expected nuclear reaction byproducts.[5] By late 1989, most scientists considered cold fusion claims dead,[6][7] and cold fusion subsequently gained a reputation as pathological science.[8][9] In 1989 the United States Department of Energy (DOE) concluded that the reported results of excess heat did not present convincing evidence of a useful source of energy and decided against allocating funding specifically for cold fusion. A second DOE review in 2004, which looked at new research, reached similar conclusions and did not result in DOE funding of cold fusion.[10] Presently, since articles about cold fusion are rarely published in peer-reviewed mainstream scientific journals, they do not attract the level of scrutiny expected for mainstream scientific publications.[11]

Nevertheless, some interest in cold fusion has continued through the decades—for example, a Google-funded failed replication attempt was published in a 2019 issue of Nature.[12][13] A small community of researchers continues to investigate it,[6][14][15] often under the alternative designations low-energy nuclear reactions (LENR) or condensed matter nuclear science (CMNS).[16][17][18][19]

- ^ "60 Minutes: Once Considered Junk Science, Cold Fusion Gets A Second Look By Researchers", CBS, 17 April 2009, archived from the original on 12 February 2012

- ^ Fleischmann & Pons 1989, p. 301 ("It is inconceivable that this [amount of heat] could be due to anything but nuclear processes... We realise that the results reported here raise more questions than they provide answers...")

- ^ a b Voss 1999a

- ^ Browne 1989, para. 1

- ^ Browne 1989, Close 1992, Huizenga 1993, Taubes 1993

- ^ a b Browne 1989

- ^ Taubes 1993, pp. 262, 265–266, 269–270, 273, 285, 289, 293, 313, 326, 340–344, 364, 366, 404–406, Goodstein 1994, Van Noorden 2007, Kean 2010

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (25 March 2004), "US will give cold fusion a second look", The New York Times, retrieved 8 February 2009

- ^ Ouellette, Jennifer (23 December 2011), "Could Starships Use Cold Fusion Propulsion?", Discovery News, archived from the original on 7 January 2012

- ^ US DOE 2004, Choi 2005, Feder 2005

- ^ Goodstein 1994, Labinger & Weininger 2005, p. 1919

- ^ Koziol, Michael (22 March 2021). "Whether Cold Fusion or Low-Energy Nuclear Reactions, U.S. Navy Researchers Reopen Case". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Berlinguette, C.P.; Chiang, YM.; Munday, J.N.; et al. (2019). "Revisiting the cold case of cold fusion". Nature. 570 (7759): 45–51. Bibcode:2019Natur.570...45B. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1256-6. PMID 31133686. S2CID 167208748.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Broad1989bwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Goodstein 1994, Platt 1998, Voss 1999a, Beaudette 2002, Feder 2005, Adam 2005 "Advocates insist that there is just too much evidence of unusual effects in the thousands of experiments since Pons and Fleischmann to be ignored", Kruglinski 2006, Van Noorden 2007, Alfred 2009. Daley 2004 calculates between 100 and 200 researchers, with damage to their careers.

- ^ "'Cold fusion' rebirth? New evidence for existence of controversial energy source", American Chemical Society, archived from the original on 21 December 2014

- ^ Hagelstein et al. 2004

- ^ "ICMNS FAQ". International Society of Condensed Matter Nuclear Science. Archived from the original on 3 November 2015.

- ^ Biberian 2007