| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Taxation |

|---|

|

| An aspect of fiscal policy |

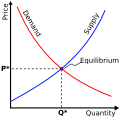

Congestion pricing or congestion charges is a system of surcharging users of public goods that are subject to congestion through excess demand, such as through higher peak charges for use of bus services, electricity, metros, railways, telephones, and road pricing to reduce traffic congestion; airlines and shipping companies may be charged higher fees for slots at airports and through canals at busy times. Advocates claim this pricing strategy regulates demand, making it possible to manage congestion without increasing supply.

According to the economic theory behind congestion pricing, the objective of this policy is to use the price mechanism to cover the social cost of an activity where users otherwise do not pay for the negative externalities they create (such as driving in a congested area during peak demand). By setting a price on an over-consumed product, congestion pricing encourages the redistribution of the demand in space or in time, leading to more efficient outcomes.

Singapore was the first country to introduce congestion pricing on its urban roads in 1975, and was refined in 1998. Since then, it has been implemented in cities such as London, Stockholm, Milan, and Gothenburg. It has also been proposed in San Francisco, and was supposed to be implemented in New York City in June 2024. Greater awareness of the harms of pollution and emissions of greenhouse gases in the context of climate change has recently created greater interest in congestion pricing.

Implementation of congestion pricing has reduced congestion in urban areas,[1] reduced pollution,[2] reduced asthma,[3] and increased house values,[4] but has also sparked criticism and public discontent. Critics maintain that congestion pricing is not equitable, places an economic burden on neighboring communities, and adversely affects retail businesses and general economic activity.

There is a consensus among economists that congestion pricing in crowded transportation networks, and subsequent use of the proceeds to lower other taxes, makes the average citizen better off.[5] Economists disagree over how to set tolls, how to cover common costs, what to do with any excess revenues, whether and how "losers" from tolling previously free roads should be compensated, and whether to privatize highways.[6] Four general types of systems are in use: a cordon area around a city center, with charges for passing the cordon line; area wide congestion pricing, which charges for being inside an area; a city center toll ring, with toll collection surrounding the city; and corridor or single facility congestion pricing, where access to a lane or a facility is priced.

- ^ "What is Congestion Pricing? - Congestion Pricing - FHWA Office of Operations". Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Retrieved 2021-12-18.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Tang, Cheng Keat (2021-01-01). "The Cost of Traffic: Evidence from the London Congestion Charge". Journal of Urban Economics. 121: 103302. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2020.103302. hdl:10356/146475. ISSN 0094-1190. S2CID 209687332.

- ^ "Congestion Pricing". Clark Center Forum. Retrieved 2023-12-09.

- ^ Lindsey, Robin (May 2006). "Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Road Pricing? The Intellectual History of an Idea" (PDF). Econ Journal Watch. 3 (2): 292–379. Retrieved 2008-12-09.