| Part of the Cold War | |

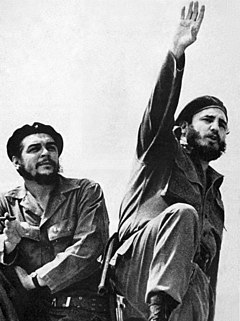

Che Guevara (left) and Fidel Castro (right) in 1961 | |

| Date | 1959–1962 |

|---|---|

| Location | Cuba |

| Outcome | Series of events including...

|

| History of Cuba |

|---|

|

| Governorate of Cuba (1511–1519) |

|

|

| Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821) |

|

|

| Captaincy General of Cuba (1607–1898) |

|

|

| US Military Government (1898–1902) |

|

|

| Republic of Cuba (1902–1959) |

|

|

| Republic of Cuba (1959–) |

|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

|

|

The consolidation of the Cuban Revolution is a period in Cuban history typically defined as starting in the aftermath of the revolution in 1959 and ending in 1962, after the total political consolidation of Fidel Castro as the maximum leader of Cuba. The period encompasses early domestic reforms, human rights violations, and the ousting of various political groups.[1][2][3][4] This period of political consolidation climaxed with the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, which then cooled much of the international contestation that arose alongside Castro's bolstering of power.[5]

The political consolidation of Fidel Castro in the new Cuban government began in early 1959. It began with the appointment of communist officials to office and a wave of removals of other revolutionaries that criticized the appointment of communists. This trend came to a head with the Huber Matos affair and would continue that by mid-1960 little opposition remained to Castro within the government and few independent institutions existed in Cuba.[6][7]

As Castro's rule became more entrenched, between 1959 and 1960, Cuba's relationship with the United States began to falter. In the immediate aftermath of the 1959 revolution, Castro visited the United States to ask for aid and boast of land reform plans, which he believed the U.S. government would appreciate. Throughout 1960 tensions slowly escalated between Cuba and the United States due to the nationalizations of various American companies, retaliatory economic sanctions, and counterrevolutionary bombing raids. In January 1961, the U.S. cut off diplomatic relations with Cuba, and the Soviet Union started to solidify relations with Cuba. The U.S. feared growing Soviet influence in Cuba and backed the Bay of Pigs Invasion of April 1961, which later failed. By December 1961, Castro for the first time openly expressed his communist sympathies. Castro's fears of another invasion and his new Soviet allies influenced his decision to put nuclear missiles in Cuba, triggering the Cuban Missile Crisis.[8] In the aftermath of the crisis, the United States promised not to invade Cuba in the future; in compliance with this agreement, the U.S. withdrew all support from the Alzados, effectively crippling the resource-starved resistance.[9] The counterrevolutionary conflict, known abroad as the Escambray rebellion, lasted until about 1965, and has since been branded as the "Struggle Against Bandits" by the Cuban government.[9]

There are various historiographical interpretations of the political consolidation that occurred between 1959 and 1962. There is a periodization of these events, as the beginning of the "militarization of Cuba" which includes a long process of domestic militarization which climaxed in 1970.[10][11] There is the "grassroots dictatorship" model, which argues that the removal of liberal rights after the Cuban Revolution was the result of mass support and citizen deputization. This mass support came from a popular enthusiasm for national defense against American invasion.[12][13] There is also the "betrayal thesis" which posits that the political consolidation of Fidel Castro was a betrayal of the democratic aims of the Cuban Revolution against Batista.[14]

- ^ Hellinger, Daniel (2014). Comparative Politics of Latin America Democracy at Last?. Taylor and Francis. p. 289. ISBN 9781134070077.

- ^ Staten, Clifford (2005). The History of Cuba. St. Martin's Press. pp. 69–105. ISBN 9781403962591.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Whalen, Charles (1975). Cuba Study Mission A Fact-finding Survey, June 26 – July 2, 1975. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 3.

- ^ Henken, Ted; Celaya, Miriam; Castellanos, Dimas (2013). Cuba. ABC-CLIO. p. 93. ISBN 9781610690126.

- ^ Lawson, George (2013). Anatomies of Revolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9781108587808.

- ^ Beyond the Eagle's Shadow New Histories of Latin America's Cold War. University of New Mexico Press. 2013. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0826353696.

- ^ Moore, Robin (2006). Music and Revolution Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba. University of California Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0520247116.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

impactwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Cuba: Intelligence and the Bay of Pigs". Stanford University. 26 September 2002. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Cuba's Forgotten Decade How the 1970s Shaped the Revolution. Lexington Books. 2018. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9781498568746.

- ^ Horowitz, Irving Louis (January 1995). Cuban Communism/8th Editi. Transaction Publisher. p. 585. ISBN 9781412820899.

- ^ Dictators and Autocrats Securing Power Across Global Politics. Taylor & Francis. 2021. p. (Section 4). ISBN 9781000467604.

- ^ Tarrago, Rafael (2017). Understanding Cuba as a Nation From European Settlement to Global Revolutionary Mission. Taylor & Francis. p. 99. ISBN 9781315444475.

- ^ Welch, Richard (October 2017). Response to Revolution The United States and the Cuban Revolution, 1959-1961. University of North Carolina Press. p. 141. ISBN 9781469610467.