It has been suggested that this article be merged into European debt crisis. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2024. |

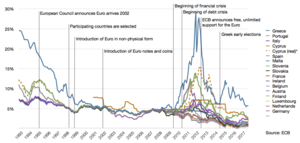

The eurozone crisis is an ongoing financial crisis that has made it difficult or impossible for some countries in the euro area to repay or re-finance their government debt without the assistance of third parties.

The European sovereign debt crisis resulted from a combination of complex factors, including the globalization of finance; easy credit conditions during the 2002–2008 period that encouraged high-risk lending and borrowing practices; the financial crisis of 2007–08; international trade imbalances; real-estate bubbles that have since burst; fiscal policy choices related to government revenues and expenses; and approaches used by nations to bail out troubled banking industries and private bondholders, assuming private debt burdens or socializing losses. [1][2]

One narrative describing the causes of the crisis begins with the significant increase in savings available for investment during the 2000–2007 period when the global pool of fixed-income securities increased from approximately $36 trillion in 2000 to $70 trillion by 2007. This "Giant Pool of Money" increased as savings from high-growth developing nations entered global capital markets. Investors searching for higher yields than those offered by U.S. Treasury bonds sought alternatives globally.[3]

The temptation offered by such readily available savings overwhelmed the policy and regulatory control mechanisms in country after country, as lenders and borrowers put these savings to use, generating bubble after bubble across the globe. While these bubbles have burst, causing asset prices (e.g., housing and commercial property) to decline, the liabilities owed to global investors remain at full price, generating questions regarding the solvency of governments and their banking systems.[1]

How each European country involved in this crisis borrowed and invested the money varies. For example, Ireland's banks lent the money to property developers, generating a massive property bubble. When the bubble burst, Ireland's government and taxpayers assumed private debts. In Greece, the government increased its commitments to public workers in the form of extremely generous wage and pension benefits, with the former doubling in real terms over 10 years.[4] Iceland's banking system grew enormously, creating debts to global investors (external debts) several times GDP.[1][5]

The interconnection in the global financial system means that if one nation defaults on its sovereign debt or enters into recession putting some of the external private debt at risk, the banking systems of creditor nations face losses. For example, in October 2011, Italian borrowers owed French banks $366 billion (net). Should Italy be unable to finance itself, the French banking system and economy could come under significant pressure, which in turn would affect France's creditors and so on. This is referred to as financial contagion.[6][7] Another factor contributing to interconnection is the concept of debt protection. Institutions entered into contracts called credit default swaps (CDS) that result in payment should default occur on a particular debt instrument (including government issued bonds). But, since multiple CDSs can be purchased on the same security, it is unclear what exposure each country's banking system now has to CDS.[8]

Greece hid its growing debt and deceived EU officials with the help of derivatives designed by major banks.[9][10][11][12][13][14] Although some financial institutions clearly profited from the growing Greek government debt in the short run,[9] there was a long lead-up to the crisis.

The European bailouts are largely about shifting exposure from banks and others, who otherwise are lined up for losses on the sovereign debt they have piled up, onto European taxpayers.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

- ^ a b c Lewis, Michael (2011). Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-08181-7.

- ^ Lewis, Michael (26 September 2011). "Touring the Ruins of the Old Economy". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "NPR-The Giant Pool of Money-May 2008". Thisamericanlife.org. 9 May 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Heard on Fresh Air from WHYY (4 October 2011). "NPR-Michael Lewis-How the Financial Crisis Created a New Third World-October 2011". Npr.org. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Michael (April 2009). "Wall Street on the Tundra". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

In the end, Icelanders amassed debts amounting to 850 percent of their G.D.P. (The debt-drowned United States has reached just 350 percent.)

- ^ Feaster, Seth W.; Schwartz, Nelson D.; Kuntz, Tom (22 October 2011). "NYT-It's All Connected-A Spectators Guide to the Euro Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012 – via nytimes.com.

- ^ XAQUÍN, G.V.; McLean, Alan; Tse, Archie (22 October 2011). "NYT-It's All Connected-An Overview of the Euro Crisis-October 2011". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ "The Economist-No Big Bazooka-29 October 2011". The Economist. 29 October 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ a b Story, Louise; Landon Thomas Jr; Schwartz, Nelson D. (14 February 2010). "Wall St. Helped to Mask Debt Fueling Europe's Crisis". The New York Times. New York. pp. A1. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Merkel Slams Euro Speculation, Warns of 'Resentment' (Update 1)". BusinessWeek. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 26 February 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Knight, Laurence (22 December 2010). "Europe's Eastern Periphery". BBC. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "PIIGS Definition". investopedia.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Riegert, Bernd. "Europe's next bankruptcy candidates?". dw-world.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Philippas, Nikolaos D. Ζωώδη Ένστικτα και Οικονομικές Καταστροφές (in Greek). skai.gr. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Featherstone, Kevin (23 March 2012). "Are the European banks saving Greece or saving themselves?". Greece@LSE. LSE. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "Greek aid will go to the banks". Die Gazette. Presseurop. 9 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Whittaker, John (2011). "Eurosystem debts, Greece, and the role of banknotes" (PDF). Lancaster University Management School. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Reich, Robert (10 May 2011). "Follow the Money: Behind Europe's Debt Crisis Lurks Another Giant Bailout of Wall Street". Social Europe Journal. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Janssen, Ronald (28 March 2012). "The Mystery Tour of Restructuring Greek Sovereign Debt". Social Europe Journal. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Roubini, Nouriel (7 March 2012). "Greece's Private Creditors Are the Lucky Ones". Financial Times. The A-List. Retrieved 28 March 2012.