Between 1788 and 1868 the British penal system transported about 162,000 convicts from Great Britain and Ireland to various penal colonies in Australia.[1]

The British Government began transporting convicts overseas to American colonies in the early 18th century. After trans-Atlantic transportation ended with the start of the American Revolution, authorities sought an alternative destination to relieve further overcrowding of British prisons and hulks. Earlier in 1770, James Cook had charted and claimed possession of the east coast of Australia for Britain. Seeking to pre-empt the French colonial empire from expanding into the region, Britain chose Australia as the site of a penal colony, and in 1787, the First Fleet of eleven convict ships set sail for Botany Bay, arriving on 20 January 1788 to found Sydney, New South Wales, the first European settlement on the continent. Other penal colonies were later established in Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) in 1803 and Queensland in 1824.[2] Western Australia – established as the Swan River Colony in 1829 – initially was intended solely for free settlers, but commenced receiving convicts in 1850. South Australia and Victoria, established in 1836 and 1850 respectively, officially remained free colonies. However, a population that included thousands of convicts already resided in the area that became known as Victoria.

Penal transportation to Australia peaked in the 1830s and dropped off significantly in the following decade, as protests against the convict system intensified throughout the colonies. In 1868, almost two decades after transportation to the eastern colonies had ceased, the last convict ship arrived in Western Australia.[3]

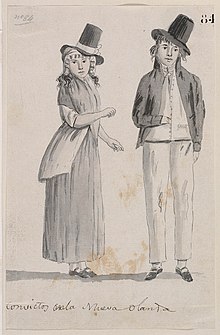

The majority of convicts were transported for petty crimes, particularly theft: thieves comprised 80% of all transportees.[4] More serious crimes, such as rape and murder, became transportable offences in the 1830s, but since they were also punishable by death, comparatively few convicts were transported for such crimes.[5] Approximately 1 in 7 convicts were women, while political prisoners, another minority group, comprised many of the best-known convicts. Once emancipated, most ex-convicts stayed in Australia and joined the free settlers, with some rising to prominent positions in Australian society. However, convictism carried a social stigma and, for some later Australians, being of convict descent instilled a sense of shame and cultural cringe. Attitudes became more accepting in the 20th century, and it is now considered by many Australians to be a cause for celebration to discover a convict in one's lineage.[6] In 2007, it was estimated that approximately four million Australians are related to convicts that were deported from the British Isles to Australia.[7] The convict era has inspired famous novels, films, and other cultural works, and the extent to which it has shaped Australia's national character has been studied by many writers and historians.[8]

- ^ "Convicts and the British colonies in Australia". Government of Australia. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "Australasian Politics". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. Vol. XXIV, no. 1258. 11 November 1826. p. 2. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Godfrey, Barry; Williams, Lucy (10 January 2018). "Australia's last living convict bucked the trend of reoffending". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Litvak, Leon. "Criminality and its Penalties in Victorian Times". Queen's University Belfast. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "Crimes of Convicts transported to Australia". Convict Records. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Barlass, Tim (20 February 2019). "Descendants of mostly convicts and they're proud of it" Archived 20 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Online records highlight Australia's convict past" Archived 25 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, ABC News (25 July 2007). Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Hirst, John (July 2008). "An Oddity From the Start: Convicts and National Character" Archived 27 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Monthly. Retrieved 4 May 2015.