This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 23,000 words. (February 2023) |

| Cooper's hawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Astur |

| Species: | A. cooperii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Astur cooperii (Bonaparte, 1828)

| |

| |

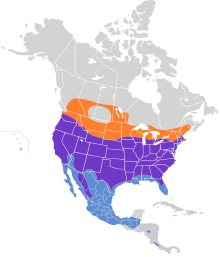

Breeding Year-round Non-breeding

| |

Cooper's hawk (Astur cooperii) is a medium-sized hawk native to the North American continent and found from southern Canada to Mexico.[2] This species was formerly placed in the genus Accipiter. As in many birds of prey, the male is smaller than the female.[3] The birds found east of the Mississippi River tend to be larger on average than the birds found to the west.[4] It is easily confused with the smaller but similar sharp-shinned hawk. (Accipiter striatus)

The species was named in 1828 by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in honor of his friend and fellow ornithologist, William Cooper.[5] Other common names for Cooper's hawk include: big blue darter, chicken hawk, flying cross, hen hawk, quail hawk, striker, and swift hawk.[6] Many of the names applied to Cooper's hawks refer to their ability to hunt large and evasive prey using extremely well-developed agility. This species primarily hunts small-to-medium-sized birds, but will also commonly take small mammals and sometimes reptiles.[7][8]

Like most related hawks, Cooper's hawks prefer to nest in tall trees with extensive canopy cover and can commonly produce up to two to four fledglings depending on conditions.[2][5] Breeding attempts may be compromised by poor weather, predators and anthropogenic causes, in particular the use of industrial pesticides and other chemical pollution in the 20th century.[7][9] Despite declines due to manmade causes, the bird remains a stable species.[1]

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Accipiter cooperii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22695656A93521264. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695656A93521264.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. (2001). Raptors of the World. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0-7136-8026-3.

- ^ Snyder, N. F., & Wiley, J. W. (1976). Sexual size dimorphism in hawks and owls of North America (No. 20). American Ornithologists' Union.

- ^ Pearlstine, E. V., & Thompson, D. B. (2004). Geographic variation in morphology of four species of migratory raptors. Journal of Raptor Research, 38(4), 334–342.

- ^ a b Palmer, R. S., ed. (1988). Handbook of North American birds. Volume 5 Diurnal Raptors (part 2).

- ^ Bent, A. C. 1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey, Part 1. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 170:295–357.

- ^ a b Rosenfield, R. N., K. K. Madden, J. Bielefeldt & Curtis, O.E. (2019). Cooper's Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), version 3.0. In The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- ^ Toland, Brian (1985). "Food Habits and Hunting Success of Cooper's Hawks in Missouri" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 56 (4): 419–422. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Snyder, N. F. R. (1974). Can the Cooper's Hawk survive? National Geographic Magazine, 145:432–442.