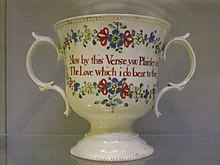

Creamware is a cream-coloured refined earthenware with a lead glaze over a pale body, known in France as faïence fine,[1] in the Netherlands as Engels porselein, and in Italy as terraglia inglese.[2] It was created about 1750 by the potters of Staffordshire, England, who refined the materials and techniques of salt-glazed earthenware towards a finer, thinner, whiter body with a brilliant glassy lead glaze, which proved so ideal for domestic ware that it supplanted white salt-glaze wares by about 1780. It was popular until the 1840s.[3]

Variations of creamware were known as "tortoiseshell ware" or "Whieldon ware" were developed by the master potter Thomas Whieldon with coloured stains under the glaze.[2] It served as an inexpensive substitute for the soft-paste porcelains being developed by contemporary English manufactories, initially in competition with Chinese export porcelains. It was often made in the same fashionable and refined styles as porcelain.

The most notable producer of creamware was Josiah Wedgwood, who perfected the ware, beginning during his partnership with Thomas Whieldon. Wedgwood supplied his creamware to Queen Charlotte and Catherine the Great (in the famous Frog Service) and used the trade name Queen's ware.[2] Later, around 1779, he was able to lighten the cream colour to a bluish white by using cobalt in the lead overglaze. Wedgwood sold this more desirable product under the name pearl ware.[2] The Leeds Pottery (producing "Leedsware") was another very successful producer.[2]

Wedgwood and his English competitors sold creamware throughout Europe, sparking local industries, that largely replaced tin-glazed faience.[4] and to the United States.[5] One contemporary writer and friend of Wedgwood claimed it was ubiquitous.[6] This led to local industries developing throughout Europe to meet demand.[7] There was also a strong export market to the United States.[8] The success of creamware had killed the demand for tin-glazed earthenware and pewter vessels alike and the spread of cheap, good-quality, mass-produced creamware to Europe had a similar impact on Continental tin-glazed faience factories.[9] By the 1780s Josiah Wedgwood was exporting as much as 80% of his output to Europe.[10]

- ^ Tamara Préaud, curator. 1997.The Sėvres Porcelain Manufactory: Alexandre Brongniart and the Triumph of Art and Industry (Bard Graduate Center, New York), Glossary, s.v. "Creamware: "In France it was known as faïence fine.

- ^ a b c d e Osborne, 140

- ^ The standard monograph is Donald C. Towner, Creamware (Faber & Faber) 1978

- ^ Jana Kybalova, European Creamware. 1989/

- ^ Osborne, 140; Creamware for the American market is the subject of Patricia A. Halfpenny, Robert S. Teitelman and Ronald Fuchs, Success to America: Creamware for the American Market 2010.

- ^ Simeon Shaw, The Chemistry of the several natural and artificial heterogeneous compounds used in manufacturing porcelain, glass, and pottery, etc.. London: for the author (1837), p. 465

- ^ Donald Towner, Creamware, London: Faber & Faber (1978) ISBN 0 571 04964 8, Chapter 10

- ^ Patricia A Halfpenny, Robert S Teitelman and Ronald Fuchs, Success to America: Creamware for the American Market. Woodbridge: Antiquw Collectors Club (2010) ISBN 978 1851496310

- ^ Jana Kybalova, European Creamware. London: Hamlyn (1989)

- ^ Robin Hildyard, English Pottery 1620 – 1840, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 93