| Cuban Missile Crisis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution | |||||||

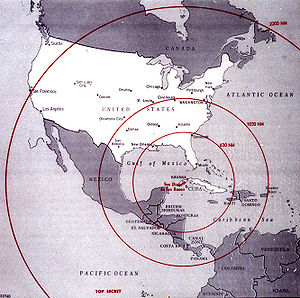

US intelligence map showing their estimates of the range of the missiles stationed in Cuba | |||||||

| |||||||

| Parties involved in the crisis | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| 100,000–180,000 (estimated) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

| ||||||

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (Spanish: Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (Russian: Карибский кризис, romanized: Karibskiy krizis), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of nuclear missiles in Italy and Turkey were matched by Soviet deployments of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis lasted from 16 to 28 October 1962. The confrontation is widely considered the closest the Cold War came to escalating into full-scale nuclear war.[1]

In 1961 the US government put Jupiter nuclear missiles in Italy and Turkey. It had trained a paramilitary force of expatriate Cubans, which the CIA led in an attempt to invade Cuba and overthrow its government. Starting in November of that year, the US government engaged in a violent campaign of terrorism and sabotage in Cuba, referred to as the Cuban Project, which continued throughout the first half of the 1960s. The Soviet administration was concerned about a Cuban drift towards China, with which the Soviets had an increasingly fractious relationship. In response to these factors the Soviet and Cuban governments agreed, at a meeting between leaders Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro in July 1962, to place nuclear missiles on Cuba to deter a future US invasion. Construction of launch facilities started shortly thereafter.

A U-2 spy plane captured photographic evidence of medium- and long-range launch facilities in October. US President John F. Kennedy convened a meeting of the National Security Council and other key advisers, forming the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM). Kennedy was advised to carry out an air strike on Cuban soil in order to compromise Soviet missile supplies, followed by an invasion of the Cuban mainland. He chose a less aggressive course in order to avoid a declaration of war. On 22 October Kennedy ordered a naval blockade to prevent further missiles from reaching Cuba.[2] He referred to the blockade as a "quarantine", not as a blockade, so the US could avoid the formal implications of a state of war.[3]

An agreement was eventually reached between Kennedy and Khrushchev. Publicly, the Soviets would dismantle their offensive weapons in Cuba, subject to United Nations verification, in exchange for a US public declaration and agreement not to invade Cuba again. Secretly, the United States agreed to dismantle all of the offensive weapons it had deployed to Turkey. There has been debate on whether Italy was also included in the agreement. While the Soviets dismantled their missiles, some Soviet bombers remained in Cuba, and the United States kept the naval quarantine in place until 20 November 1962.[3][4] The blockade was formally ended on 20 November after all offensive missiles and bombers had been withdrawn from Cuba. The evident necessity of a quick and direct communication line between the two powers resulted in the Moscow–Washington hotline. A series of agreements later reduced US–Soviet tensions for several years.

The compromise embarrassed Khrushchev and the Soviet Union because the withdrawal of US missiles from Italy and Turkey was a secret deal between Kennedy and Khrushchev, and the Soviets were seen as retreating from a situation that they had started. Khrushchev's fall from power two years later was in part because of the Soviet Politburo's embarrassment at both Khrushchev's eventual concessions to the US and his ineptitude in precipitating the crisis. According to the Soviet Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin, the top Soviet leadership took the Cuban outcome as "a blow to its prestige bordering on humiliation".[5][6]

- ^ Scott, Len; Hughes, R. Gerald (2015). The Cuban Missile Crisis: A Critical Reappraisal. Taylor & Francis. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-317-55541-4. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Society, National Geographic (21 April 2021). "Kennedy 'Quarantines' Cuba". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ a b Colman, Jonathan (1 May 2019). "Toward 'World Support' and 'The Ultimate Judgment of History': The U.S. Legal Case for the Blockade of Cuba during the Missile Crisis, October–November 1962". Journal of Cold War Studies. 21 (2): 150–173. doi:10.1162/jcws_a_00879. ISSN 1520-3972.

- ^ "Milestones: 1961–1968 – The Cuban Missile Crisis, October 1962". history.state.gov. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019.

- ^ William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (2004) p. 579.

- ^ Jeffery D. Shields (7 March 2016). "The Malin Notes: Glimpses Inside the Kremlin during the Cuban Missile Crisis" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.