| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

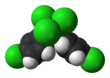

| Preferred IUPAC name

1,1′-(2,2,2-Trichloroethane-1,1-diyl)bis(4-chlorobenzene) | |||

| Other names

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)

Clofenotane | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.023 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C14H9Cl5 | |||

| Molar mass | 354.48 g·mol−1 | ||

| Density | 0.99 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 108.5 °C (227.3 °F; 381.6 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 260 °C (500 °F; 533 K) (decomposes) | ||

| 25 μg/L (25 °C)[1] | |||

| Pharmacology | |||

| QP53AB01 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Toxic, dangerous to the environment, suspected carcinogen | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H301, H350, H372, H410 | |||

| P201, P202, P260, P264, P270, P273, P281, P301+P310, P308+P313, P314, P321, P330, P391, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 72–77 °C; 162–171 °F; 345–350 K[3] | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

113–800 mg/kg (rat, oral)[1] 250 mg/kg (rabbit, oral) 135 mg/kg (mouse, oral) 150 mg/kg (guinea pig, oral)[2] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits):[4] | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 1 mg/m3 [skin] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

Ca TWA 0.5 mg/m3 | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

500 mg/m3 | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, is a colorless, tasteless, and almost odorless crystalline chemical compound,[5] an organochloride. Originally developed as an insecticide, it became infamous for its environmental impacts. DDT was first synthesized in 1874 by the Austrian chemist Othmar Zeidler. DDT's insecticidal action was discovered by the Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller in 1939. DDT was used in the second half of World War II to limit the spread of the insect-borne diseases malaria and typhus among civilians and troops. Müller was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1948 "for his discovery of the high efficiency of DDT as a contact poison against several arthropods".[6] The WHO's anti-malaria campaign of the 1950s and 1960s relied heavily on DDT and the results were promising, though there was a resurgence in developing countries afterwards.[7][8]

By October 1945, DDT was available for public sale in the United States. Although it was promoted by government and industry for use as an agricultural and household pesticide, there were also concerns about its use from the beginning.[9] Opposition to DDT was focused by the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring. It talked about environmental impacts that correlated with the widespread use of DDT in agriculture in the United States, and it questioned the logic of broadcasting potentially dangerous chemicals into the environment with little prior investigation of their environmental and health effects. The book cited claims that DDT and other pesticides caused cancer and that their agricultural use was a threat to wildlife, particularly birds. Although Carson never directly called for an outright ban on the use of DDT, its publication was a seminal event for the environmental movement and resulted in a large public outcry that eventually led, in 1972, to a ban on DDT's agricultural use in the United States.[10] Along with the passage of the Endangered Species Act, the United States ban on DDT is a major factor in the comeback of the bald eagle (the national bird of the United States) and the peregrine falcon from near-extinction in the contiguous United States.[11][12]

The evolution of DDT resistance and the harm both to humans and the environment led many governments to curtail DDT use.[13] A worldwide ban on agricultural use was formalized under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, which has been in effect since 2004. Recognizing that total elimination in many malaria-prone countries is currently unfeasible in the absence of affordable/effective alternatives for disease control, the convention exempts public health use within World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines from the ban.[14]

DDT still has limited use in disease vector control because of its effectiveness in killing mosquitos and thus reducing malarial infections, but that use is controversial due to environmental and health concerns.[15][16] DDT is one of many tools to fight malaria, which remains the primary public health challenge in many countries. WHO guidelines require that absence of DDT resistance must be confirmed before using it.[17] Resistance is largely due to agricultural use, in much greater quantities than required for disease prevention.[17]

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

ATSDRc5was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "DDT". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0174". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards".

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

EHC009was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology of Medicine 1948". Nobel Prize Outreach AB. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

DDTBP.1/2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Feachem2007was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Distillationswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lear, Linda (2009). Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature. Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-547-23823-4. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- ^ Stokstad E (June 2007). "Species conservation. Can the bald eagle still soar after it is delisted?". Science. 316 (5832): 1689–1690. doi:10.1126/science.316.5832.1689. PMID 17588911. S2CID 5051469.

- ^ United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Fact Sheet: Natural History, Ecology, and History of Recovery [1] Archived May 21, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chapin81was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Stockholmwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Larson K (December 1, 2007). "Bad Blood". On Earth (Winter 2008). Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ Moyers B (September 21, 2007). "Rachel Carson and DDT". Bill Moyers Journal. PBS. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

IRS-WHOwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).