Native name: 出島 | |

|---|---|

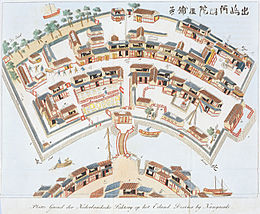

An imagined bird's-eye view of Dejima's layout and structures (copied from a woodblock print by Toshimaya Bunjiemon of 1780 and published in Isaac Titsingh's Bijzonderheden over Japan (1824/25) | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Nagasaki |

| Administration | |

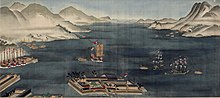

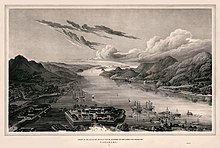

Dejima (Japanese: 出島, lit. 'exit island') or Deshima,[a] in the 17th century also called Tsukishima (築島, lit. 'built island'), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1858).[1] For 220 years, it was the central conduit for foreign trade and cultural exchange with Japan during the isolationist Edo period (1600–1869), and the only Japanese territory open to Westerners.[2]

Spanning 120 m × 75 m (390 ft × 250 ft) or 9,000 m2 (2.2 acres), Dejima was created in 1636 by digging a canal through a small peninsula and linking it to the mainland with a small bridge. The island was constructed by the Tokugawa shogunate, whose isolationist policies sought to preserve the existing sociopolitical order by forbidding outsiders from entering Japan while prohibiting most Japanese from leaving. Dejima housed European merchants and separated them from Japanese society while still facilitating lucrative trade with the West.

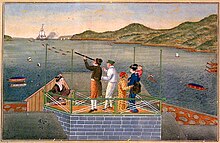

Following a rebellion by mostly Catholic converts, the Portuguese were expelled in 1639. The Dutch were moved to Dejima in 1641, under stricter control and scrutiny, and segregated from Japanese society. The open practice of Christianity was banned, and interactions between Dutch and Japanese traders were tightly regulated, with only a small number of foreign merchants being allowed to disembark in Dejima. Until the mid-19th century, the Dutch were the only Westerners with exclusive access to the Japanese markets. Dejima consequently played a key role in the Japanese movement of rangaku (蘭學, Dutch learning), an organized scholarly effort to learn the Dutch language in order to understand Western science, medicine, and technology.[3]

After the 1854 Treaty of Kanagawa set a precedent for more fully opening Japan to foreign trade and diplomatic relations, the Dutch negotiated their own treaty in 1858, which ended Dejima's status as exclusive trading post, greatly reducing its importance. The island was eventually subsumed into Nagasaki city through land reclamation. In 1922, the "Dejima Dutch Trading Post" was designated a Japanese national historic site, and there are ongoing efforts in the 21st century to restore Dejima as an island.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ "Dejima Nagasaki | JapanVisitor Japan Travel Guide". www.japanvisitor.com. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ^ Goss, Rob. "The Wild West Outpost of Japan's Isolationist Era". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- ^ "rangaku | Japanese history | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-06-25.