Delft | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

A view of Delft with the Oude Kerk in the centre | |

| Nickname: Prinsenstad (Prince City) | |

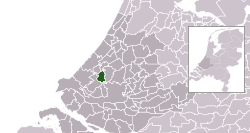

Location in South Holland | |

| Coordinates: 52°0′42″N 4°21′33″E / 52.01167°N 4.35917°E | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Province | South Holland |

| City Hall | Delft City Hall |

| Government | |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Mayor | Marja van Bijsterveldt (CDA) |

| Area | |

• Total | 24.06 km2 (9.29 sq mi) |

| • Land | 22.65 km2 (8.75 sq mi) |

| • Water | 1.41 km2 (0.54 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (January 2021)[4] | |

• Total | 103,581 |

| • Density | 4,573/km2 (11,840/sq mi) |

| Demonyms |

|

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postcodes | 2600–2629 |

| Area code | 015 |

| Website | www |

Delft (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈdɛl(ə)ft] ) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. It is located between Rotterdam, to the southeast, and The Hague, to the northwest. Together with them, it is a part of both the Rotterdam–The Hague metropolitan area and the Randstad.

Delft is a popular tourist destination in the Netherlands, famous for its historical connections with the reigning House of Orange-Nassau, for its blue pottery, for being home to the painter Jan Vermeer, and for hosting Delft University of Technology (TU Delft). Historically, Delft played a highly influential role in the Dutch Golden Age.[5][6][7][8] In terms of science and technology, thanks to the pioneering contributions of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek[9][10] and Martinus Beijerinck,[11] Delft can be considered to be the birthplace of microbiology.

- ^ "Maak kennis met" [Meet.]. Burgermeester Verkerk (in Dutch). Gemeente Delft. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ "Kerncijfers wijken en buurten 2020" [Key figures for neighbourhoods 2020]. StatLine (in Dutch). CBS. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Postcodetool for 2611GX". Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland (in Dutch). Het Waterschapshuis. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ "Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand" [Population growth; regions per month]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Huerta, Robert D.: Giants of Delft: Johannes Vermeer and the Natural Philosophers: The Parallel Search for Knowledge during the Age of Discovery. (Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press, 2003)

- ^ Brook, Timothy: Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World. (Bloomsbury Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1596915992)

- ^ Liedtke, Walter; Plomp, Michiel C.; Rüger, Axel; Baarsen, Reinier J.: Vermeer and the Delft School. (NYC: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013, ISBN 978-0300200294)

- ^ Snyder, Laura J.: Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing. (W. W. Norton & Company, 2015, ISBN 978-0393352887)

- ^ Ruestow, Edward G.: The Microscope in the Dutch Republic: The Shaping of Discovery. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

- ^ Fournier, Marian: The Fabric of Life: The Rise and Decline of Seventeenth-Century Microscopy. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0801851384)

- ^ Artenstein, Andrew W.: The discovery of viruses: advancing science and medicine by challenging dogma. (International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 16, Issue 7, July 2012, pages: e470-e473). doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2012.03.005. Andrew W. Artenstein: "By 1895 Beijerinck had returned to academia after leaving the Agricultural School for a 10-year stint in industrial microbiology in Delft, the South Holland birthplace of van Leeuwenhoek, one of the founding fathers of microbiology. During his first years at the Technical University of Delft, Beijerinck resumed the research on tobacco mosaic disease that he had started while working with Mayer. Even then, he had appreciated that the affliction was microbial in nature, although he felt that the actual agents had yet to be discovered. Beijerinck's investigations at Delft proved fruitful; he not only confirmed the infectivity of the contagium vivum fluidum—soluble living germ—despite filtration, but he importantly demonstrated that unlike bacteria, the culprit of tobacco disease of plants was incapable of independent growth, requiring the presence of living, dividing host cells in order to replicate."