| Dengue fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dengue, breakbone fever[1][2] |

| |

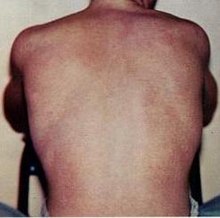

| Typical rash seen in dengue fever | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, rash. Can be severe, mild or asymptomatic[1][2] |

| Complications | Bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, dangerously low blood pressure[2] |

| Usual onset | 3–14 days after exposure[2] |

| Duration | 2–7 days[1] |

| Causes | Dengue virus by Aedes mosquitos[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Malaria, yellow fever, viral hepatitis, leptospirosis[5] |

| Prevention | Dengue fever vaccine, decreasing mosquito exposure[1][6] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, intravenous fluids, blood transfusions[2] |

| Frequency | 5 million per year (2023)[7] |

| Deaths | 5,000 per year (2023)[7] |

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne disease caused by dengue virus, prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas. It is frequently asymptomatic; if symptoms appear they typically begin 3 to 14 days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin itching and skin rash. Recovery generally takes two to seven days. In a small proportion of cases, the disease develops into severe dengue (previously known as dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome)[8] with bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, blood plasma leakage, and dangerously low blood pressure.[1][2]

Dengue virus has four confirmed serotypes; infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term immunity to the others. Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe complications.[9] The symptoms of dengue resemble many other diseases including malaria, influenza, and Zika.[10] Blood tests are available to confirm the diagnosis including detecting viral RNA, or antibodies to the virus.[11]

There is no specific treatment for dengue fever. In mild cases, treatment is focused on treating pain symptoms. Severe cases of dengue require hospitalisation; treatment of acute dengue is supportive and includes giving fluid either by mouth or intravenously.[1][2]

Dengue is spread by several species of female mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, principally Aedes aegypti.[1] Infection can be prevented by mosquito elimination and the prevention of bites.[12] Two types of dengue vaccine have been approved and are commercially available. Dengvaxia became available in 2016 but it is only recommended to prevent re-infection in individuals who have been previously infected.[13] The second vaccine, Qdenga, became available in 2022 and is suitable for adults, adolescents and children from four years of age.[14]

The earliest descriptions of a dengue outbreak date from 1779; its viral cause and spread were understood by the early 20th century.[15] Already endemic in more than one hundred countries, dengue is spreading from tropical and subtropical regions to the Iberian Peninsula and the southern states of the US, partly attributed to climate change.[7][16] It is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[17] During 2023, more than 5 million infections were reported, with more than 5,000 dengue-related deaths.[7] As most cases are asymptomatic or mild, the actual numbers of dengue cases and deaths are under-reported.[7]

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Dengue and severe dengue". World Health Organization. 17 March 2023. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kularatne SA (September 2015). "Dengue fever". BMJ. 351: h4661. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4661. PMID 26374064. S2CID 1680504.

- ^ dengue Archived 17 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- ^ dengue in Oxford Dictionaries

- ^ Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics: The field of pediatrics. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2016. p. 1631. ISBN 978-1-4557-7566-8. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ East S (6 April 2016). "World's first dengue fever vaccine launched in the Philippines". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Dengue- Global situation". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ Alejandria MM (April 2015). "Dengue haemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome in children". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2015: 0917. PMC 4392842. PMID 25860404.

- ^ "Dengue | CDC Yellow Book 2024". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 May 2023. Archived from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Schaefer TJ, Panda PK, Wolford RW (14 November 2022). "Dengue Fever". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28613483. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "Dengue Diagnosis | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "Dengue: How to keep children safe | UNICEF South Asia". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ "Dengue vaccine: WHO position paper – September 2018" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 36 (93): 457–76. 7 September 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Qdenga | European Medicines Agency". European Medicines Agency. 16 December 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Henchal EA, Putnak JR (October 1990). "The dengue viruses". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 3 (4): 376–396. doi:10.1128/CMR.3.4.376. PMC 358169. PMID 2224837.

- ^ Paz-Bailey G, Adams LE, Deen J, Anderson KB, Katzelnick LC (February 2024). "Dengue". Lancet. 403 (10427): 667–682. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02576-X. PMID 38280388. S2CID 267201333.

- ^ "Neglected tropical diseases". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.