This article has an unclear citation style. (April 2019) |

| Computer memory and data storage types |

|---|

| Volatile |

| Non-volatile |

Dynamic random-access memory (dynamic RAM or DRAM) is a type of random-access semiconductor memory that stores each bit of data in a memory cell, usually consisting of a tiny capacitor and a transistor, both typically based on metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) technology. While most DRAM memory cell designs use a capacitor and transistor, some only use two transistors. In the designs where a capacitor is used, the capacitor can either be charged or discharged; these two states are taken to represent the two values of a bit, conventionally called 0 and 1. The electric charge on the capacitors gradually leaks away; without intervention the data on the capacitor would soon be lost. To prevent this, DRAM requires an external memory refresh circuit which periodically rewrites the data in the capacitors, restoring them to their original charge. This refresh process is the defining characteristic of dynamic random-access memory, in contrast to static random-access memory (SRAM) which does not require data to be refreshed. Unlike flash memory, DRAM is volatile memory (vs. non-volatile memory), since it loses its data quickly when power is removed. However, DRAM does exhibit limited data remanence.

DRAM typically takes the form of an integrated circuit chip, which can consist of dozens to billions of DRAM memory cells. DRAM chips are widely used in digital electronics where low-cost and high-capacity computer memory is required. One of the largest applications for DRAM is the main memory (colloquially called the RAM) in modern computers and graphics cards (where the main memory is called the graphics memory). It is also used in many portable devices and video game consoles. In contrast, SRAM, which is faster and more expensive than DRAM, is typically used where speed is of greater concern than cost and size, such as the cache memories in processors.

The need to refresh DRAM demands more complicated circuitry and timing than SRAM. This is offset by the structural simplicity of DRAM memory cells: only one transistor and a capacitor are required per bit, compared to four or six transistors in SRAM. This allows DRAM to reach very high densities with a simultaneous reduction in cost per bit. Refreshing the data consumes power and a variety of techniques are used to manage the overall power consumption. For this reason, DRAM is usually needed to operate with a memory controller; memory controller needs to know DRAM parameters especially memory timings to initiaze DRAMs, which maybe different depend on different DRAM manufacturers and part numbers.

DRAM had a 47% increase in the price-per-bit in 2017, the largest jump in 30 years since the 45% jump in 1988, while in recent years the price has been going down.[3] In 2018, a "key characteristic of the DRAM market is that there are currently only three major suppliers — Micron Technology, SK Hynix and Samsung Electronics" that are "keeping a pretty tight rein on their capacity".[4] There is also Kioxia (previously Toshiba Memory Corporation after 2017 spin-off) which doesn't manufacture DRAM. Other manufacturers make and sell DIMMs (but not the DRAM chips in them), such as Kingston Technology, and some manufacturers that sell stacked DRAM (used e.g. in the fastest supercomputers on the exascale), separately such as Viking Technology. Others sell such integrated into other products, such as Fujitsu into its CPUs, AMD in GPUs, and Nvidia, with HBM2 in some of their GPU chips.

- ^ "How to "open" microchip and what's inside? : ZeptoBars". 2012-11-15. Archived from the original on 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

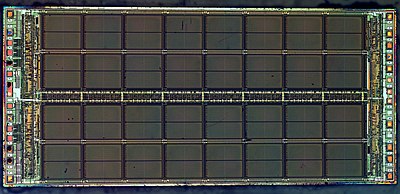

Micron MT4C1024 — 1 mebibit (220 bit) dynamic ram. Widely used in 286 and 386-era computers, early 90s. Die size - 8662x3969μm.

- ^ "NeXTServiceManualPages1-160" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ "Are the Major DRAM Suppliers Stunting DRAM Demand?". www.icinsights.com. Archived from the original on 2018-04-16. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ EETimes; Hilson, Gary (2018-09-20). "DRAM Boom and Bust is Business as Usual". EETimes. Retrieved 2022-08-03.