This article needs to be updated. (August 2021) |

Nicaragua's economic history has shifted from concentration in gold, beef, and coffee to a mixed economy under the Sandinista government to an International Monetary Fund policy attempt in 1990.

Pre-Columbian Nicaragua had a well-developed agrarian society. European diseases and forced work in gold mines decimated the native population. Most tilled land reverted to jungle. Beef, hides, and tallow were the colony's principal exports. Commercial coffee growing began in the 1840s, expanding to resemble a banana republic at the end of the 19th century. After World War II, the economy diversified, with new crops and industrialization. In the 1960s, the Central American Common Market and import substitution industrialization stimulated the economy. The 1972 earthquake destroyed much of Nicaragua's industrial infrastructure. Reconstruction led to high foreign indebtedness, with the benefits concentrated in a few hands, especially the Somoza family.

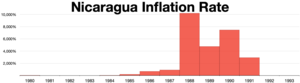

The Sandinista government was determined to make workers and peasants the prime beneficiaries. All land belonging to the Somozas was confiscated, though private property continued in a mixed economy. Restructuring and rebuilding caused initial growth, but GDP dropped from 1984 to 1990. Between decreasing revenues, mushrooming military expenditures, and printing large amounts of paper money, inflation peaked at 14,000% annually in 1987. In early 1988, the Daniel Ortega administration established austerity with price controls and a new currency. Then the government spent massively to repair Hurricane Joan damage. A US embargo also hindered economic development. In 1990, most Nicaraguans were considerably poorer than in the 1970s.

The Chamorro administration embraced International Monetary Fund and World Bank policy with the Mayoraga Plan. The plan aimed to halt spiraling inflation, lower the fiscal deficit, reduce the public sector and military work force, reduce social spending, attract foreign investment, and encourage exports. Loss of jobs and higher prices resulted in crippling public and private-sector strikes. By the end of 1990, most free market reforms were abandoned. A severe drought in 1992 decimated the principal export crops and a tsunami left thousands homeless. Foreign aid and investment had not returned in significant amounts.