| Thermoregulation in animals |

|---|

|

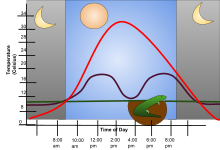

An ectotherm (from the Greek ἐκτός (ektós) "outside" and θερμός (thermós) "heat"), more commonly referred to as a "cold-blooded animal",[1] is an animal in which internal physiological sources of heat, such as blood, are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.[2] Such organisms (frogs, for example) rely on environmental heat sources,[3] which permit them to operate at very economical metabolic rates.[4]

Some of these animals live in environments where temperatures are practically constant, as is typical of regions of the abyssal ocean and hence can be regarded as homeothermic ectotherms. In contrast, in places where temperature varies so widely as to limit the physiological activities of other kinds of ectotherms, many species habitually seek out external sources of heat or shelter from heat; for example, many reptiles regulate their body temperature by basking in the sun, or seeking shade when necessary in addition to a whole host of other behavioral thermoregulation mechanisms.

In contrast to ectotherms, endotherms rely largely, even predominantly, on heat from internal metabolic processes, and mesotherms use an intermediate strategy.

As there are more than two categories of temperature control utilized by animals, the terms warm-blooded and cold-blooded have been deprecated as scientific terms.

- ^ "Ectotherm | Definition, Advantages, & Examples | Britannica".

- ^ Davenport, John. Animal Life at Low Temperature. Publisher: Springer 1991. ISBN 978-0412403507

- ^ Jay M. Savage; with photographs by Michael Fogden and Patricia Fogden. (2002). The Amphibians and Reptiles of Costa Rica: a Herpetofauna Between Two Continents, Between Two Seas. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-226-73538-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Milton Hildebrand; G. E. Goslow, Jr. Principal ill. Viola Hildebrand. (2001). Analysis of vertebrate structure. New York: Wiley. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-471-29505-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)