Edward Oxford | |

|---|---|

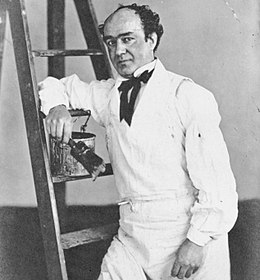

Oxford, c. 1857 | |

| Born | 19 April 1822 Birmingham, Warwickshire, England |

| Died | 23 April 1900 (aged 78) Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Known for | Attempted regicide of Queen Victoria |

| Criminal charge | High treason |

| Spouse |

Jane Bowen (m. 1881) |

Edward Oxford (19 April 1822 – 23 April 1900) was an English man who attempted to assassinate Queen Victoria in 1840. He was the first of seven unconnected people who tried to kill her between 1840 and 1882. Born and raised in Birmingham, he showed erratic behaviour which was sometimes threatening or violent. He had a series of jobs in pubs, all of which he lost because of his conduct. In 1840, shortly after being dismissed from yet another pub, he purchased two pistols and fired twice at Queen Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert. No-one was hurt.

Oxford was arrested and charged with high treason. A jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity and he was detained indefinitely at Her Majesty's pleasure at the two State Criminal Lunatic Asylums: first at Bethlem Royal Hospital and then, after 1864, Broadmoor Hospital. Visitors and staff did not consider him insane.

In 1867 Oxford was given the offer of release if he relocated to a British colony; he accepted and settled in Melbourne, Australia, under the new name "John Freeman". He worked as a decorator, married and became a respected figure at his local church. He began writing stories on the seedier aspects of Melbourne life for The Argus, which were published under the pseudonym "Liber". He later published a book, Lights and Shadows of Melbourne Life, which looks at both the wealthy and seamy parts of Melbourne.

Oxford's trial, and the later M'Naghten case led to an overhaul of the law on criminal insanity in England. In January 1843 Daniel M'Naghten murdered Edward Drummond—the private secretary to the Prime Minister—mistaking him for the Prime Minister, Robert Peel. Like Oxford, M'Naghten was also found not guilty on the grounds of insanity. The cases of Oxford and M'Naghten prompted the judiciary to frame the M'Naghten rules on instructions to be given to a jury for a defence of insanity.