E. C. Boudinot | |

|---|---|

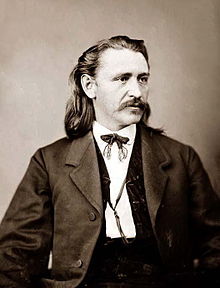

Boudinot, c. 1860 | |

| Delegate to the C.S. House of Representatives from the Cherokee Nation's at-large district | |

| In office February 18, 1862 – May 10, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Elias Cornelius Boudinot August 1, 1835 New Echota, Cherokee Nation (present-day Gordon County, Georgia), U.S. |

| Died | September 27, 1890 (aged 55) Fort Smith, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Cemetery, Fort Smith, Arkansas, U.S. 35°22′10.3″N 94°24′06.8″W / 35.369528°N 94.401889°W |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Clara C. Boudinot (m. 1885) |

| Parent(s) | Elias Boudinot (father) Harriet Boudinot (mother) |

| Relatives | Stand Watie (uncle) |

| Education | Burr Seminary |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States |

| Branch | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1862 |

| Rank | Major |

| Unit | 2d Cherokee Mounted Rifles |

| Battles | |

Elias Cornelius Boudinot (August 1, 1835 – September 27, 1890) was an American politician, lawyer, newspaper editor, and co-founder of the Arkansan who served as the delegate to the Confederate States House of Representatives representing the Cherokee Nation. Prior to this he served as an officer of the Confederate States Army in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. He was the first Native American lawyer permitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court.[1]

He was the mixed-race son of Elias and Harriet Ruggles (née Gold) Boudinot, who was from Connecticut. His father was editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper, which was published in Cherokee and English. In 1839 his father and three other leaders were assassinated by opponents in the tribe as retaliation for having ceded their homeland in the 1835 Treaty of New Echota. The Boudinot children were orphaned by their father's murder, as their mother had died in 1836. They were sent for their safety to their mother's family in Connecticut, where they were educated.

Following the Civil War, Boudinot participated in negotiations of the Southern Cherokee with the United States before the tribe was reunited; he was part of the Cherokee delegation to the US. In 1868 he and his uncle Stand Watie opened a tobacco factory, to take advantage of provisions under the nation's new 1866 treaty with the United States. It was confiscated for non-payment of taxes, and their case went to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled against them. Boudinot began to lobby for Native Americans to be granted United States citizenship in order to be protected by the Constitution.

He was active in politics and society in the Indian Territory and Washington, D.C., supporting construction of railroads in the territory. Boudinot also worked for two Arkansas politicians. He supported proposals for termination of Cherokee sovereignty and the allotment of communal land to tribal members, as was passed under the Dawes Act. As this would extinguish tribal land rights, Boudinot also worked to establish the state of Oklahoma and have it admitted to the Union. In his 2011 history of America's transcontinental railroads, historian Richard White writes of Boudinot: "[He] became a willing tool of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad.... If the competition were not so stiff, Boudinot might be ranked among the great scoundrels of the Gilded Age."[2]

- ^ "Widow of Indian Lawyer, Former Resident of Washington". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. September 25, 1911. p. 18. Retrieved June 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Richard White (2011). Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. National Geographic Books. ISBN 978-0-393-34237-6.