Elmore Leonard | |

|---|---|

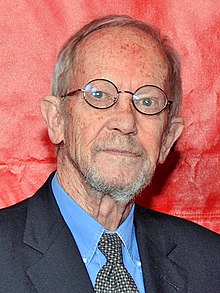

Leonard at the 70th Annual Peabody Awards Luncheon, 2011 | |

| Born | Elmore John Leonard Jr. October 11, 1925 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | August 20, 2013 (aged 87) Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Alma mater | University of Detroit |

| Genre | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 5, including Peter |

| Relatives | Megan Freels Johnston (granddaughter) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1943–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

Elmore John Leonard Jr. (October 11, 1925 – August 20, 2013) was an American novelist, short story writer, and screenwriter. His earliest novels, published in the 1950s, were Westerns, but he went on to specialize in crime fiction and suspense thrillers, many of which have been adapted into motion pictures. Among his best-known works are Hombre, Swag, City Primeval, LaBrava, Glitz, Freaky Deaky, Get Shorty, Rum Punch, Out of Sight and Tishomingo Blues.

Leonard's short story "Three-Ten to Yuma" was adapted as 3:10 to Yuma, which was remade in 2007. Rum Punch was adapted as the Quentin Tarantino film Jackie Brown (1997). Steven Soderbergh adapted Out of Sight in 1998 into a film of the same name. Get Shorty was adapted into an eponymous film in 1995, and in 2017 it was adapted into a television series of the same name. His writings were also the basis for The Tall T, as well as the FX television series Justified and Justified: City Primeval. Among other honors, he won the 2009 Pen Lifetime Award[1] and the 2012 Medal For Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.[2][3]

Anthony Lane of The New Yorker wrote that Leonard

was hailed as one of the best crime writers in the land. High praise, but not quite high enough, and some way off the mark. He was one of the best writers, and he happened to write about crime. Even that is not entirely accurate. It's true that his novels (more than forty of them, with another left unfinished at his death) enjoyed the company of criminals and of those who tried to stop them in their tracks. This was seldom hard, since, as Leonard delighted in showing us, crime—more than anything, even politics—allows men of all ages to disport themselves across the full range of human ineptitude. Boy, do they screw up.[4]

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 30, 2009). "Pen Lifetime Award For Elmore Leonard". The New York Times.

- ^ Bosman, Julie (September 19, 2012). "Elmore Leonard to Be Honored by National Book Foundation". The New York Times.

- ^ "For Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, National Book Foundation, medal, 2012". archives.library.sc.edu. 2012.

- ^ Lane, Anthony (August 21, 2013). "The Dutch Accent: Elmore Leonard's Talk". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2018.