| Regarding the Status of Slaves in States Engaged in Rebellion Against the United States | |

| |

Emancipation: The Past and the Future (Th. Nast, 1863) | |

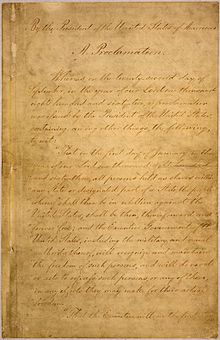

The five-page original document, held in the National Archives Building – until 1936 it had been bound with other proclamations in a large volume held by the Department of State[1] | |

| Other short titles | Emancipation Proclamation |

|---|---|

| Type | Presidential proclamation |

| Executive Order number | unnumbered |

| Signed by | Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862 |

| Federal Register details | |

| Publication date | 1 January 1863 |

| Summary | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal Political 16th President of the United States First term Second term Presidential elections Speeches and works

Assassination and legacy  |

||

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95,[2][3] was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the effect of changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to "be received into the armed service of the United States". The Emancipation Proclamation played a significant part in the end of slavery in the United States.

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.[4] Its third paragraph begins:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation.[5] It stated:

I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do ... order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion, against the United States, the following, to wit:

Lincoln then listed the ten states[6] still in rebellion, excluding parts of states under Union control, and continued:

I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free. ... [S]uch persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States. ... And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

The proclamation provided that the executive branch, including the Army and Navy, "will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons".[7] Even though it excluded states not in rebellion, as well as parts of Louisiana and Virginia under Union control,[8] it still applied to more than 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country. Around 25,000 to 75,000 were immediately emancipated in those regions of the Confederacy where the US Army was already in place. It could not be enforced in the areas still in rebellion,[8] but, as the Union army took control of Confederate regions, the Proclamation provided the legal framework for the liberation of more than three and a half million enslaved people in those regions by the end of the war. The Emancipation Proclamation outraged white Southerners and their sympathizers, who saw it as the beginning of a race war. It energized abolitionists, and undermined those Europeans who wanted to intervene to help the Confederacy.[9] The Proclamation lifted the spirits of African Americans, both free and enslaved. It encouraged many to escape from slavery and flee toward Union lines, where many joined the Union Army.[10] The Emancipation Proclamation became a historic document because it "would redefine the Civil War, turning it [for the North] from a struggle [solely] to preserve the Union to one [also] focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict."[11]

The Emancipation Proclamation was never challenged in court. To ensure the abolition of slavery in all of the U.S., Lincoln also insisted that Reconstruction plans for Southern states require them to enact laws abolishing slavery (which occurred during the war in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana); Lincoln encouraged border states to adopt abolition (which occurred during the war in Maryland, Missouri, and West Virginia) and pushed for passage of the 13th Amendment. The Senate passed the 13th Amendment by the necessary two-thirds vote on April 8, 1864; the House of Representatives did so on January 31, 1865; and the required three-fourths of the states ratified it on December 6, 1865. The amendment made slavery and involuntary servitude unconstitutional, "except as a punishment for a crime".[12]

- ^ "Featured Document: The Emancipation Proclamation". n.d.

- ^ "Proclamation 95—Regarding the Status of Slaves in States Engaged in Rebellion Against the United States [Emancipation Proclamation] | The American Presidency Project". presidency.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on December 18, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Harward, Brian (2020). The Presidency in Times of Crisis and Disaster: Primary Documents in Context. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-44-087088-0. Archived from the original on April 23, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Text of Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

- ^ Text of Emancipation Proclamation

- ^ Eleven states had seceded, but Tennessee was under Union control.

- ^ Dirck, Brian R. (2007). The Executive Branch of Federal Government: People, Process, and Politics. ABC-CLIO. p. 102. ISBN 978-1851097913.

The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order, itself a rather unusual thing in those days. Executive orders are simply presidential directives issued to agents of the executive department by its boss.

- ^ a b Davis, Kenneth C. (2003). Don't Know Much About History: Everything You Need to Know About American History but Never Learned (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-06-008381-6.

- ^ Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union, vol. 6: War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863 (1960) pp. 231–241, 273

- ^ Jones, Howard (1999). Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War. University of Nebraska Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-8032-2582-2.

- ^ "Emancipation Proclamation". History. January 6, 2020. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ "13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution". The Library of Congress. Retrieved June 27, 2013.