| Esophageal achalasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Achalasia cardiae, cardiospasm, esophageal aperistalsis, achalasia |

| |

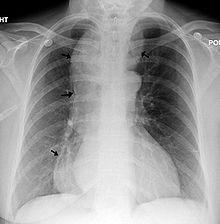

| A chest X-ray showing achalasia (arrows point to the outline of the massively dilated esophagus) | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, thoracic surgery, general surgery, laparoscopic surgery |

| Symptoms | Anorexia (but willing and trying to eat), inability to swallow food, chest pain comparable to heart attack, lightheadedness, dehydration, excessive vomiting after eating (often without nausea). |

| Usual onset | Normally in mid-to-late life, rarely during youth |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | 1st stage – 2–3 cm dilated,

2nd stage – 4–5 cm dilated, bird beak looking, 3rd stage – 5–7 cm, dilated 4th / Late-stage – 8+ cm dilated, sigmoid |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Risk factors | Inconclusive, but possibly: history of autoimmune disorders, air-hunger that accompanies anxiety, faulty eating habits, improper diet |

| Diagnostic method | Esophageal manometry, biopsy, X-ray, barium swallow study, endoscopy |

| Prevention | No method of prevention |

| Treatment | Heller myotomy and fundoplomy, POEM, pneumatic dilation, botulinum toxin |

| Prognosis | ~76% chance of survival after 20 years (in a western country such as Germany)[2] |

| Frequency | ~1 in 100,000 people[2] |

| Deaths | 829 in a period of 1–8 years study out of a 28 demographic, 754 million record pool.[3] |

Esophageal achalasia, often referred to simply as achalasia, is a failure of smooth muscle fibers to relax, which can cause the lower esophageal sphincter to remain closed. Without a modifier, "achalasia" usually refers to achalasia of the esophagus. Achalasia can happen at various points along the gastrointestinal tract; achalasia of the rectum, for instance, may occur in Hirschsprung's disease. The lower esophageal sphincter is a muscle between the esophagus and stomach that opens when food comes in. It closes to avoid stomach acids from coming back up. A fully understood cause to the disease is unknown, as are factors that increase the risk of its appearance. Suggestions of a genetically transmittable form of achalasia exist, but this is neither fully understood, nor agreed upon.[4]

Esophageal achalasia is an esophageal motility disorder involving the smooth muscle layer of the esophagus and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).[5] It is characterized by incomplete LES relaxation, increased LES tone, and lack of peristalsis of the esophagus (inability of smooth muscle to move food down the esophagus) in the absence of other explanations like cancer or fibrosis.[6][7][8]

Achalasia is characterized by difficulty in swallowing, regurgitation, and sometimes chest pain. Diagnosis is reached with esophageal manometry and barium swallow radiographic studies. Various treatments are available, although none cures the condition. Certain medications or botox may be used in some cases, but more permanent relief is brought by esophageal dilatation and surgical cleaving of the muscle (Heller myotomy or POEM).

The most common form is primary achalasia, which has no known underlying cause. It is due to the failure of distal esophageal inhibitory neurons. However, a small proportion occurs secondary to other conditions, such as esophageal cancer, Chagas disease (an infectious disease common in South America) or Triple-A syndrome.[9] Achalasia affects about one person in 100,000 per year.[9][10] There is no gender predominance for the occurrence of disease.[11] The term is from a- + -chalasia "no relaxation."

Achalasia can also manifest alongside other diseases as a rare syndrome such as achalasia microcephaly.[12]

- ^ ACHALASIA | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com

- ^ a b Tanaka S, Abe H, Sato H, Shiwaku H, Minami H, Sato C, et al. (October 2021). "Frequency and clinical characteristics of special types of achalasia in Japan: A large-scale, multicenter database study". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 36 (10): 2828–2833. doi:10.1111/jgh.15557. PMID 34032322. S2CID 235200001.

- ^ Mayberry JF, Newcombe RG, Atkinson M (April 1988). "An international study of mortality from achalasia". Hepato-Gastroenterology. 35 (2): 80–82. PMID 3259530.

- ^ "Achalasia".

- ^ Park W, Vaezi MF (June 2005). "Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 100 (6): 1404–1414. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41775.x. PMID 15929777. S2CID 33583131.

- ^ Spechler SJ, Castell DO (July 2001). "Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities". Gut. 49 (1): 145–151. doi:10.1136/gut.49.1.145. PMC 1728354. PMID 11413123.

- ^ Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ (January 2005). "AGA technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry". Gastroenterology. 128 (1): 209–224. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.008. PMID 15633138.

- ^ Pandolfino JE, Gawron AJ (May 2015). "Achalasia: a systematic review". JAMA. 313 (18): 1841–1852. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2996. PMID 25965233.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Spiesswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lakewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Francis DL, Katzka DA (August 2010). "Achalasia: update on the disease and its treatment". Gastroenterology. 139 (2): 369–374. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.024. PMID 20600038.

- ^ Gockel HR, Schumacher J, Gockel I, Lang H, Haaf T, Nöthen MM (October 2010). "Achalasia: will genetic studies provide insights?". Human Genetics. 128 (4): 353–364. doi:10.1007/s00439-010-0874-8. PMID 20700745. S2CID 583462.