In the United States Electoral College, a faithless elector is generally a party representative who does not have faith in the election result within their region and instead votes for another person for one or both offices, or abstains from voting. As part of United States presidential elections, each state legislates the method by which its electors are to be selected. Many states require electors to have pledged to vote for the candidates of their party if appointed. The consequences of an elector voting in a way inconsistent with their pledge vary from state to state.

Electors are typically chosen and nominated by a political party or the party's presidential nominee, and are usually party members with a reputation for high loyalty to the party and its chosen candidate. Thus, a faithless elector runs the risk of party censure and political retaliation from their party, as well as potential legal penalties in some states. Candidates for electors are nominated by state political parties in the months prior to Election Day. In some states, such as Indiana, the electors are nominated in primaries, the same way other candidates are nominated.[2] In other states, such as Oklahoma, Virginia, and North Carolina, electors are nominated in party conventions. In Pennsylvania, the campaign committee of each candidate names their candidates for elector in an attempt to discourage faithless electors. In some states, high-ranking or well-known state officials up to and including governors often serve as electors whenever possible (the Constitution prohibits federal officials from acting as electors, but does not restrict state officials from doing so). The parties have generally been successful in keeping their electors faithful, leaving out the rare cases in which a candidate died before the elector was able to cast a vote.[citation needed]

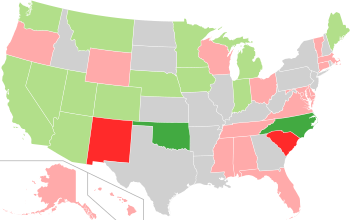

As of the 2020 election, there have been a total of 165[3][4] instances of faithlessness, 90 of which were for president, while 75 were for vice president. They have never swung an election,[4] and nearly all have voted for third party candidates or non-candidates, as opposed to switching their support to a major opposing candidate. There were 63 faithless electors in 1872 when Horace Greeley died between Election Day and when the Electoral College convened, but Ulysses S. Grant had already clinched enough to win reelection. During the 1836 election, Virginia's entire 23-man electoral delegation faithlessly abstained[why?][5] from voting for victorious Democratic vice presidential nominee Richard M. Johnson.[3] The loss of Virginia's support caused Johnson to fall one electoral vote short of a majority, causing the vice-presidential race to be thrown into the U.S. Senate under a contingent election. The presidential election itself was not in dispute because Virginia's electors voted for Democratic presidential nominee Martin Van Buren as pledged. The Senate elected Johnson as vice president anyway after a party-line vote. Uniquely, Richard Nixon always had a faithless elector in one of his state slates during his three runs for President. Oklahoma in 1960, North Carolina in 1968 and Virginia in 1972 all voted for Nixon but one elector cast a vote for another person.

The United States Constitution does not specify a notion of pledging; no federal law or constitutional statute binds an elector's vote to anything. All pledging laws originate at the state level;[6][7] the U.S. Supreme Court upheld these state laws in its 1952 ruling Ray v. Blair. In 2020, the Supreme Court also ruled in Chiafalo v. Washington that states are free to enforce laws that bind electors to voting for the winner of the popular vote in their state.[8]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

lawswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "About the Electors". National Archives and Records Administration. August 27, 2019.

- ^ a b "Faithless Electors". Fair Vote. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "Electoral College Cements Joe Biden's Victory With Zero Faithless Electors". Newsweek. December 14, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

SabatoErnst2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Openshaw, Pamela Romney (2014). Promises Of The Constitution: Yesterday Today Tomorrow. BookBaby. p. 10.3. ISBN 9781483529806.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ross, Tara (2017). The Indispensable Electoral College: How the Founders' Plan Saves Our Country from Mob Rule. Gateway Editions. p. 26. ISBN 9781621577072.

- ^ "Justices rule states can bind presidential electors' votes". Associated Press. July 6, 2020.