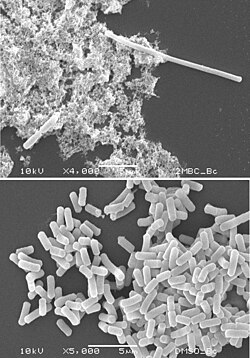

Filamentation is the anomalous growth of certain bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, in which cells continue to elongate but do not divide (no septa formation).[1][2] The cells that result from elongation without division have multiple chromosomal copies.[1]

In the absence of antibiotics or other stressors, filamentation occurs at a low frequency in bacterial populations (4–8% short filaments and 0–5% long filaments in 1- to 8-hour cultures).[3] The increased cell length can protect bacteria from protozoan predation and neutrophil phagocytosis by making ingestion of cells more difficult.[1][3][4][5] Filamentation is also thought to protect bacteria from antibiotics, and is associated with other aspects of bacterial virulence such as biofilm formation.[6][7]

The number and length of filaments within a bacterial population increases when the bacteria are exposed to different physical, chemical and biological agents (e.g. UV light, DNA synthesis-inhibiting antibiotics, bacteriophages).[3][8] This is termed conditional filamentation.[2] Some of the key genes involved in filamentation in E. coli include sulA, minCD and damX.[9][10]

- ^ a b c Jaimes-Lizcano YA, Hunn DD, Papadopoulos KD (April 2014). "Filamentous Escherichia coli cells swimming in tapered microcapillaries". Research in Microbiology. 165 (3): 166–74. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2014.01.007. PMID 24566556.

- ^ a b Karasz DC, Weaver AI, Buckley DH, Wilhelm RC (January 2022). "Conditional filamentation as an adaptive trait of bacteria and its ecological significance in soils". Environmental Microbiology. 24 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.15871. OSTI 1863903. PMID 34929753. S2CID 245412965.

- ^ a b c Cushnie TP, O'Driscoll NH, Lamb AJ (December 2016). "Morphological and ultrastructural changes in bacterial cells as an indicator of antibacterial mechanism of action". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73 (23): 4471–4492. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2302-2. hdl:10059/2129. PMID 27392605. S2CID 2065821.

- ^ Hahn MW, Höfle MG (May 1998). "Grazing pressure by a bacterivorous flagellate reverses the relative abundance of Comamonas acidovorans PX54 and Vibrio strain CB5 in chemostat cocultures". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 64 (5): 1910–8. Bibcode:1998ApEnM..64.1910H. doi:10.1128/AEM.64.5.1910-1918.1998. PMC 106250. PMID 9572971.

- ^ Hahn MW, Moore ER, Höfle MG (January 1999). "Bacterial filament formation, a defense mechanism against flagellate grazing, is growth rate controlled in bacteria of different phyla". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 65 (1): 25–35. Bibcode:1999ApEnM..65...25H. doi:10.1128/AEM.65.1.25-35.1999. PMC 90978. PMID 9872755.

- ^ Justice SS, Hunstad DA, Cegelski L, Hultgren SJ (February 2008). "Morphological plasticity as a bacterial survival strategy". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 6 (2): 162–8. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1820. PMID 18157153. S2CID 7247384.

- ^ Fuchs BB, Eby J, Nobile CJ, El Khoury JB, Mitchell AP, Mylonakis E (June 2010). "Role of filamentation in Galleria mellonella killing by Candida albicans". Microbes and Infection. 12 (6): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2010.03.001. PMC 288367. PMID 20223293.

- ^ Ragunathan PT, Vanderpool CK (December 2019). "Cryptic-Prophage-Encoded Small Protein DicB Protects Escherichia coli from Phage Infection by Inhibiting Inner Membrane Receptor Proteins". Journal of Bacteriology. 201 (23). doi:10.1128/JB.00475-19. PMC 6832061. PMID 31527115.

- ^ Bi E, Lutkenhaus J (February 1993). "Cell division inhibitors SulA and MinCD prevent formation of the FtsZ ring". Journal of Bacteriology. 175 (4): 1118–1125. doi:10.1128/jb.175.4.1118-1125.1993. PMC 193028. PMID 8432706.

- ^ Khandige S, Asferg CA, Rasmussen KJ, Larsen MJ, Overgaard M, Andersen TE, Møller-Jensen J (August 2016). Justice S, Hultgren SJ (eds.). "DamX Controls Reversible Cell Morphology Switching in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli". mBio. 7 (4). doi:10.1128/mBio.00642-16. PMC 4981707. PMID 27486187.