The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, four fundamental types of answer to the question "why?" in analysis of change or movement in nature: the material, the formal, the efficient, and the final. Aristotle wrote that "we do not have knowledge of a thing until we have grasped its why, that is to say, its cause."[1][2] While there are cases in which classifying a "cause" is difficult, or in which "causes" might merge, Aristotle held that his four "causes" provided an analytical scheme of general applicability.[3]

Aristotle's word aitia (αἰτία) has, in philosophical scholarly tradition, been translated as 'cause'. This peculiar, specialized, technical, usage of the word 'cause' is not that of everyday English language.[4] Rather, the translation of Aristotle's αἰτία that is nearest to current ordinary language is "explanation."[5][2][4]

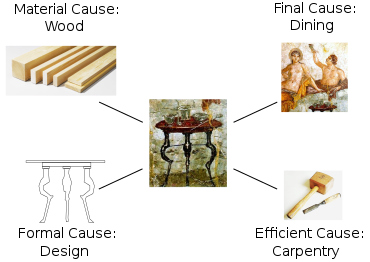

In Physics II.3 and Metaphysics V.2, Aristotle holds that there are four kinds of answers to "why" questions:[2][5][6]

- Matter

- The material cause of a change or movement. This is the aspect of the change or movement that is determined by the material that composes the moving or changing things. For a table, this might be wood; for a statue, it might be bronze or marble.

- Form

- The formal cause of a change or movement. This is a change or movement caused by the arrangement, shape, or appearance of the thing changing or moving. Aristotle says, for example, that the ratio 2:1, and number in general, is the formal cause of the octave.

- Efficient, or agent

- The efficient or moving cause of a change or movement. This consists of things apart from the thing being changed or moved, which interact so as to be an agency of the change or movement. For example, the efficient cause of a table is a carpenter, or a person working as one, and according to Aristotle the efficient cause of a child is a parent.

- Final, end, or purpose

- The final cause of a change or movement. This is a change or movement for the sake of a thing to be what it is. For a seed, it might be an adult plant; for a sailboat, it might be sailing; for a ball at the top of a ramp, it might be coming to rest at the bottom.

The four "causes" are not mutually exclusive. For Aristotle, several, preferably four, answers to the question "why" have to be given to explain a phenomenon and especially the actual configuration of an object.[7] For example, if asking why a table is such and such, an explanation in terms of the four causes would sound like this: This table is solid and brown because it is made of wood (matter); it does not collapse because it has four legs of equal length (form); it is as it is because a carpenter made it, starting from a tree (agent); it has these dimensions because it is to be used by humans (end).

Aristotle distinguished between intrinsic and extrinsic causes. Matter and form are intrinsic causes because they deal directly with the object, whereas efficient and finality causes are said to be extrinsic because they are external.[8]

Thomas Aquinas demonstrated that only those four types of causes can exist and no others. He also introduced a priority order according to which "matter is made perfect by the form, form is made perfect by the agent, and agent is made perfect by the finality."[9] Hence, the finality is the cause of causes or, equivalently, the queen of causes.[10]

- ^ Aristotle, Physics 194 b17–20; see also Posterior Analytics 71 b9–11; 94 a20.

- ^ a b c Falcon, Andrea (2019) [First published 2006]. "Aristotle on Causality: 2. The Four Causes". In Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

... for a full range of cases, an explanation which fails to invoke all four causes is no explanation at all.

- ^ Lindberg, David. 1992. The Beginnings of Western Science. p. 53.

- ^ a b Leroi 2015, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b "Aristotle famously distinguishes four 'causes' (or causal factors in explanation), the matter, the form, the end, and the agent." Hankinson, R. J. 1998. Cause and Explanation in Ancient Greek Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0198237457. doi:10.1093/0199246564.001.0001.

- ^ Aristotle. Metaphysics V, (Aristotle in 23 Volumes, vols. 17–18), translated by H. Tredennick (1933/1989). London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1989 – via Perseus Project. § 1013a. Aristotle discusses the four "causes" in his Physics, Book B, ch. 3.

- ^ According to Reece (2018): "Aristotle thinks that human action is a species of animal self-movement, and animal self-movement is a species of natural change. Natural changes, although they are not substances and do not have causes in precisely the same way that substances do, are to be explained in terms of the four causes, or as many of them as a given natural change has: The material cause is that out of which something comes to be, or what undergoes change from one state to another; the formal cause, what differentiates something from other things, and serves as a paradigm for its coming to be that thing; the efficient cause, the starting-point of change; the final cause, that for the sake of which something comes about."

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysica I. 983 a26 ss. As quoted in Battista Mondin (2022), Ontologia e Metafisica, 3rd ed., ESD, p. 157, ISBN 978-8855450539.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, In IV Sententiarum, d. 3, q. 1, a. 1. sol. 1. As quoted in Battista Mondin (2022), Ontologia e metafisica, ESD, 2022, p. 158

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 5, a. 2, ad. 1