Franco Luambo | |

|---|---|

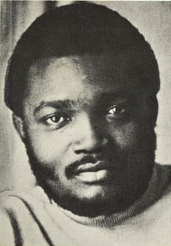

Luambo Makiadi in the early 1970s | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | François Luambo Luanzo Makiadi |

| Also known as | Franco |

| Born | 6 July 1938 Sona Bata, Belgian Congo (modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) |

| Origin | Sona-Bata |

| Died | 12 October 1989 (aged 51) Mont-Godinne, Province of Namur, Belgium |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instrument(s) | Guitar vocals |

| Years active | 1950s–1980s |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of |

|

François Luambo Luanzo Makiadi (6 July 1938 – 12 October 1989) was a Congolese singer, guitarist, songwriter, bandleader, and cultural revolutionary.[1][2][3][4] He was a central figure in 20th-century Congolese and African music, principally as the bandleader for over 30 years of TPOK Jazz, the most popular and influential African band of its time and arguably of all time.[5][6][7] He is referred to as Franco Luambo or simply Franco. Known for his mastery of African rumba, he was nicknamed by fans and critics "Sorcerer of the Guitar" and the "Grand Maître of Zairean Music", as well as Franco de Mi Amor by female fandom.[8] AllMusic described him as perhaps the "big man in African music".[9] His extensive musical repertoire was a social commentary on love, interpersonal relationships, marriage, decorum, politics, rivalries, mysticism, and commercialism.[10][11] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked him at number 71 on its list of the 250 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.[12]

Between 1952 and 1955, Luambo made his music debut as a guitarist for Bandidu, Watam, LOPADI, and Bana Loningisa.[13] In 1956, he co-founded OK Jazz (later known as TPOK Jazz), which emerged as a defining force in Congolese and African popular music.[14][15][16] As the band's leading guitarist, he assumed sole leadership in 1970 and introduced innovations to African rumba, including altering the placement of the genre's instrumental interlude sebene at the end of songs.[17] He also developed a distinct thumb-and-forefinger plucking style to create an auditory illusion of sebene's two guitar lines and established TPOK Jazz's guitar-centric lineup, often showcasing his own mi-solo, which bridges the rhythm guitar and the lead guitar.[18][19][17]

During the 1970s, Luambo became more politically involved as president Mobutu Sese Seko promoted his state ideology of Authenticité.[20][21][22] He wrote a variety of songs that praised Mobutu's regime and other political figures.[23] In 1985, Luambo and TPOK Jazz sustained their prominence with their Congolese rumba smash hit "Mario", which sold over 200,000 copies in Zaire and achieved gold certification.[24] The BBC named him among fifty African icons.[25]

- ^ Erenberg, Lewis A. (14 September 2021). The Rumble in the Jungle: Muhammad Ali and George Foreman on the Global Stage. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-226-79234-7.

- ^ Coelho, Victor, ed. (10 July 2003). The Cambridge Companion to the Guitar. Cambridge, England, United States: Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-521-00040-6.

- ^ Delmas, Adrien; Bonacci, Giulia; Argyriadis, Kali, eds. (1 November 2020). Cuba and Africa, 1959-1994: Writing an alternative Atlantic history. Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa: Wits University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-77614-633-8.

- ^ Grice, Carter (1 November 2011). ""Happy are those who sing and dance": Mobuto, Franco, and the struggle for Zairian identity". University of North Carolina Greensboro. Greensboro, North Carolina, United States. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (June 1992). Breakout: Profiles in African Rhythm. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-226-77406-0.

- ^ Mukalo, Shem. "The Legend of The Grand Maitre: How Franco Revolutionised African Music". The Standard. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Eyre, Banning (21 March 2013). "Looking Back on Franco". Afropop Worldwide. New York, New York, United States. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (3 July 2001). "Franco de Mi Amor". Village Voice. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Nickson, Chris. "AllMusic: Franco". AllMusic. Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Ngaira, Amos (5 October 2024). "Franco Luambo Luanzo Makiadi's fans mark 35 years since death". Daily Nation. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Montaz, Leo (8 March 2024). ""Lêkê", music in sandals". Pan African Music. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Franco Luambo". Rolling Stone Australia. 15 October 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Ossinondé, Clément (5 October 2009). "Le souvenir de Luambo Makiadi Franco et l'Ok Jazz" [The memory of Luambo Makiadi Franco and Ok Jazz]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Haugerud, Angelique; Stone, Margaret Priscilla; Little, Peter D., eds. (2000). Commodities and Globalization: Anthropological Perspectives. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-8476-9943-8.

- ^ Martin, Phyllis (8 August 2002). Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville. Cambridge, England, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-521-52446-9.

- ^ Ellingham, Mark; Trillo, Richard; Broughton, Simon, eds. (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. London, England, United Kingdom: Rough Guides. p. 460. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8.

- ^ a b "The mixed legacy of DRC musician Franco". New African. London, England, United Kingdom. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ The World of Music, Volume 36. Kassel, Hesse, Germany: Bärenreiter Kassel. 1994. p. 69.

- ^ Mpisi, Jean (2003). Tabu Ley "Rochereau": innovateur de la musique africaine (in French). Paris, France: Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 185. ISBN 978-2-7475-5735-1.

- ^ Ngaira, Amos (28 November 2020). "A tale of polemic music and politics in the Congo". Daily Nation. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Nkenkela, Auguste Ken (28 December 2023). "Les souvenirs de la musique congolaise: l'activisme de Luambo Makiadi Franco dans la politique et le sport au Zaïre" [Memories of Congolese Music: Luambo Makiadi Franco's Activism in Politics and Sports in Zaire]. Adiac-congo.com (in French). Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Franco: A Musician in Service of Mobutu?". Innovativeresearchmethods.org. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ White, Bob W. (27 June 2008). Rumba Rules: The Politics of Dance Music in Mobutu's Zaire. Durham, North Carolina, United States: Duke University Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-0-8223-4112-3.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- ^ "Forum: Who is your African Icon?". BBC. Broadcasting House, London, England. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2024.