| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other.[2][3] Types of friction include dry, fluid, lubricated, skin, and internal -- an incomplete list. The study of the processes involved is called tribology, and has a history of more than 2000 years.[4]

Friction can have dramatic consequences, as illustrated by the use of friction created by rubbing pieces of wood together to start a fire. Another important consequence of many types of friction can be wear, which may lead to performance degradation or damage to components. It is known that frictional energy losses account for about 20% of the total energy expenditure of the world.[5][6]

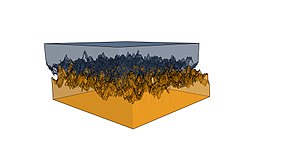

As briefly discussed later, there are many different contributors to the retarding force in friction, ranging from asperity deformation to the generation of charges and changes in local structure. Friction is not itself a fundamental force, it is a non-conservative force – work done against friction is path dependent. In the presence of friction, some mechanical energy is transformed to heat as well as the free energy of the structural changes and other types of dissipation, so mechanical energy is not conserved. The complexity of the interactions involved makes the calculation of friction from first principles difficult and it is often easier to use empirical methods for analysis and the development of theory.[3][2]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Hanaor-2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "friction". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b "Friction | Definition, Types, & Formula | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-09-11. Archived from the original on 2024-09-16. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ Ghose, Tia; published, Ailsa Harvey (2022-02-08). "What is Friction?". livescience.com. Archived from the original on 2024-05-20. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ Mitchell, Luke (November 2012). Ward, Jacob (ed.). "The Fiction of Nonfriction". Popular Science. No. 5. 281 (November 2012): 40.

- ^ Ghose, Tia; published, Ailsa Harvey (2022-02-08). "What is Friction?". livescience.com. Archived from the original on 2024-05-20. Retrieved 2024-10-07.