This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (November 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

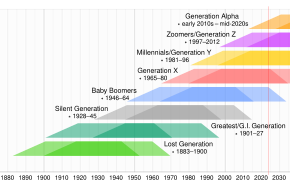

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

Generation Z (or Gen Z for short), colloquially known as Zoomers,[1][2] is the demographic cohort succeeding Millennials and preceding Generation Alpha.[3] Members of Generation Z, were born between the mid-to-late 1990s and the early 2010s, with the generation typically being defined as those born from 1997 to 2012. In other words, the first wave came of age during the second decade of the twenty-first century,[4] a time of significant demographic change due to declining birthrates, population aging, and immigration.[5] Girls of the early twenty-first century reach puberty earlier than their counterparts from the previous generations.[6] They have higher incidents of eye problems,[7][8] allergies,[9][10] awareness and reporting of mental health issues,[9][11][12] suicide,[13] and sleep deprivation,[14][15] but lower rates of adolescent pregnancy.[16][17][18] They drink alcohol and smoke traditional tobacco cigarettes less often,[19] but are more likely to consume marijuana[20][21] and electronic cigarettes.[22]

Americans who grew up in the 2000s and 2010s saw gains in IQ points,[23] but loss in creativity.[24] During the 2000s and 2010s, while Western educators in general and American schoolteachers in particular concentrated on helping struggling rather than gifted students,[25] American students of the 2010s had a decline in mathematical literacy and reading proficiency[26] and were trailing behind their counterparts from other countries, especially East Asia.[27][28] They ranked above the OECD average in science and computer literacy, but below average in mathematics.[29]

They became familiar with the Internet and portable digital devices at a young age (as "digital natives"),[4] but are not necessarily digitally literate,[30] and tend to struggle in a digital work place.[31][32] The majority use at least one social-media platform,[33] leading to concerns that spending so much time on social media can distort their view of the world,[34] hamper their social development,[35] harm their mental health,[36][37][38][39][40] expose them to inappropriate materials,[41][42] and cause them to become addicted.[33][43]

Although they trust traditional news media more than what they see online,[44] they tend to be more skeptical of the news than their parents.[45] Young Americans of the late 2010s and early 2020s tend to hold politically left-leaning views.[46][47] However, there is a significant sex gap[48] and most are more interested in advancing their careers than pursuing idealistic political causes.[49][50] As voters, Generation Z's top issue is the economy.[51] As consumers, Generation Z's actual purchases do not reflect their environmental ideals.[52][53] Members of Generation Z, especially women, are also less likely to be religious than older cohorts.[54][55]

On the whole, they are financially cautious,[56][57] and are increasingly interested in alternatives to attending institutions of higher education,[58][59] with young men being primarily responsible for the trend.[60][61] Among those who choose to go to college, grades and standards have fallen because of disruptions in learning due to COVID-19.[62]

Although American youth culture has become highly fragmented by the start of the early twenty-first century, a product of growing individualism,[63] nostalgia is a major feature of youth culture in the 2010s and 2020s.[64][65]

- ^ "Words We're Watching: 'Zoomer'". Merriam-Webster. October 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ "zoomer". Dictionary.com. January 16, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Alex (September 19, 2015). "Meet Alpha: The Next 'Next Generation'". Fashion. The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "Generation Z". Lexico. Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Pew-2018awas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Nawaz, Amna; Hudgins, Jackson. "New study details potential long-term health risks as American girls reach puberty earlier". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Stevens-2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Hellmich-2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

The Economist-2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

National Post-2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Twenge-2017awas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bethune, Sophie (January 2019). "Gen Z more likely to report mental health concerns". Monitor. 50 (1). American Psychological Association: 20.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Miron-2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Twenge-2017bwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

AAPed-2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Patten, Eileen; Livingston, Gretchen (April 29, 2016). "Why is the teen birth rate falling?". Pew Research Center. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Edwards, Erika (November 27, 2019). "U.S. birth rate falls for 4th year in a row". Health News. NBC News. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Kekatos-2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Blad-2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ayesh-2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Schepis-2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Perrone-2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Flynn, James R.; Shayer, Michael (January–February 2018). "IQ decline and Piaget: Does the rot start at the top?". Intelligence. 66: 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2017.11.010.

- ^ Kim, Kyung Hee (2011). "The Creativity Crisis: The Decrease in Creative Thinking Scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking". Creativity Research Journal. 23 (4): 285–95. doi:10.1080/10400419.2011.627805. S2CID 10855765.

- ^ Clynes, Tom (September 7, 2016). "How to raise a genius: lessons from a 45-year study of super-smart children". Nature. 537 (7619): 152–155. Bibcode:2016Natur.537..152C. doi:10.1038/537152a. PMID 27604932. S2CID 4459557.

- ^ Goldstein, Dana (December 3, 2019). "'It Just Isn't Working': Test Scores Cast Doubt on U.S. Education Efforts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ Wai, Jonathan; Makel, Matthew C. (September 4, 2015). "How do academic prodigies spend their time and why does that matter?". The Conversation. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ DeSilver, Drew (February 15, 2017). "U.S. students' academic achievement still lags that of their peers in many other countries". Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Rotermund, Susan; Burke, Amy (July 8, 2021). "Elementary and Secondary STEM Education - Executive Summary". National Science Foundation. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Strauss-2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hunter, Tatum (March 8, 2023). "What's a scanner? Gen Z is discovering workplace tech". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ^ Wells, Georgia (August 24, 2024). "Gen Z-ers Are Computer Whizzes. Just Don't Ask Them to Type". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 25, 2024. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:21was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Pincott-2022was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Haidt, Jonathan (May 2022). "Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Goldfield-2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Prinstein-2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Smyth-2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Schwartz, Casey (April 20, 2023). "Jean Twenge is ready to make you defend your generation again". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Reed-2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Pickhardt-2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gibson, Caitlin (September 25, 2024). "The dark revelations of a new documentary about teens and social media". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 25, 2024. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ Sy, Stephanie; Dubnow, Shoshana (December 26, 2023). "States suing Meta accuse company of manipulating its apps to make children addicted". PBS Newshour. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ "New Barnes & Noble Education Report Finds Gen Z Will Have Strong Influence on 2020 Presidential Election". Business Wire (via AP). June 20, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Reuters-2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Pew-2019bwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:7was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:5was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:9was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

The Economist-2023awas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

The Economist-2023bwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jones-2022was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:15was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Miller-2019cwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Solmon, Paul (May 16, 2019). "What Gen Z college grads are looking for in a career". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Solman, Paul (March 28, 2019). "Anxious about debt, Generation Z makes college choice a financial one". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "Can Gen Z Save Manufacturing from the 'Silver Tsunami'?". Industry Week. July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ Belkin, Douglas (September 6, 2021). "A Generation of American Men Give Up on College: 'I Just Feel Lost'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Thompson-2021was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Fawcett, Eliza (November 1, 2022). "The Pandemic Generation Goes to College. It Has Not Been Easy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 1, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Twenge, Jean (2023). "Chapter 1: The How and Why of Generations". Generations: The Real Differences Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X and Silents—and What The Mean for America's Future. New York: Atria Books. ISBN 978-1-9821-8161-1.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jan-2022was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Mirabelli, Gabriella (November 15, 2019). "Why Nostalgia Appeals to Younger Audiences (Guest Column)". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 14, 2024.