| Giant cell arteritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Temporal arteritis, cranial arteritis,[1] Horton disease,[2] senile arteritis,[1] granulomatous arteritis[1] |

| |

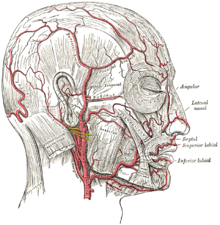

| The arteries of the face and scalp | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, emergency medicine, Immunology |

| Symptoms | Headache, pain over the temples, flu-like symptoms, double vision, difficulty opening the mouth[3] |

| Complications | Blindness, aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm, polymyalgia rheumatica[4] |

| Usual onset | Age greater than 50[4] |

| Causes | Inflammation of the small blood vessels within the walls of larger arteries[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and blood tests, confirmed by biopsy of the temporal artery[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Takayasu arteritis,[5] stroke, primary amyloidosis[6] |

| Treatment | Steroids, bisphosphonates, proton-pump inhibitor[4] |

| Prognosis | Life expectancy (typically normal)[4] |

| Frequency | ~ 1 in 15,000 people a year (> 50 years old)[2] |

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), also called temporal arteritis, is an inflammatory autoimmune disease of large blood vessels.[4][7] Symptoms may include headache, pain over the temples, flu-like symptoms, double vision, and difficulty opening the mouth.[3] Complications can include blockage of the artery to the eye with resulting blindness, as well as aortic dissection, and aortic aneurysm.[4] GCA is frequently associated with polymyalgia rheumatica.[4]

The cause is unknown.[2] The underlying mechanism involves inflammation of the small blood vessels that supply the walls of larger arteries.[4] This mainly affects arteries around the head and neck, though some in the chest may also be affected.[4][8] Diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms, blood tests, and medical imaging, and confirmed by biopsy of the temporal artery.[4] However, in about 10% of people the temporal artery is normal.[4]

Treatment is typical with high doses of steroids such as prednisone or prednisolone.[4] Once symptoms have resolved, the dose is decreased by about 15% per month.[4] Once a low dose is reached, the taper is slowed further over the subsequent year.[4] Other medications that may be recommended include bisphosphonates to prevent bone loss and a proton-pump inhibitor to prevent stomach problems.[4]

It affects about 1 in 15,000 people over the age of 50 per year.[2] The condition mostly occurs in those over the age of 50, being most common among those in their 70s.[4] Females are more often affected than males.[4] Those of northern European descent are more commonly affected.[5] Life expectancy is typically normal.[4] The first description of the condition occurred in 1890.[1]

- ^ a b c d Nussinovitch U (2017). The Heart in Rheumatic, Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases: Pathophysiology, Clinical Aspects and Therapeutic Approaches. Academic Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-12-803268-8. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b c d "Orphanet: Giant cell arteritis". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Giant Cell Arteritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 13 April 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ (July 2014). "Clinical practice. Giant-cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (1): 50–57. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1214825. PMC 4277693. PMID 24988557.

- ^ a b Johnson RJ, Feehally J, Floege J (2014). Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 300. ISBN 9780323242875. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22.

- ^ Ferri FF (2010). Ferri's Differential Diagnosis E-Book: A Practical Guide to the Differential Diagnosis of Symptoms, Signs, and Clinical Disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-323-08163-4. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22.

- ^ Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, et al. (January 2013). "2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 65 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1002/art.37715. PMID 23045170. S2CID 20891451.

- ^ "Giant Cell Arteritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 13 April 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.